Introduction

The continued expansion of co-curricular leadership initiatives offered through student affairs provides diverse opportunities for students interested in their growth as leaders. Yet, leadership education is not universally defined nor is there a common approach for teaching leadership (Brungardt, 1996; Jenkins & Owen, 2016). Hence, the leadership development of college students is an expanding area of interest and research within academic and student affairs (Burns, 1995). Much of the current research focuses on how individuals gain leadership knowledge rather than their development as leaders (Keating et al., 2014) or the developmental path chosen (Rosch et al., 2015). Research is also limited on the preparation of collegiate leadership educators (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Jenkins & Owen, 2016), within either context.

Leadership researchers from both academic and student affairs paradigms readily admit that neither has exclusive rights to leadership education. Both sides recount how leadership learning transcends the formal classroom (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Hartman et al., 2015; Jenkins & Owen, 2016), and that the leadership learning occurring outside the classroom has potential to equal the value of leadership learning within the classroom (Buschlen & Guthrie, 2014). The varied leadership development opportunities in student affairs provide a space wherein students can practice and grow their leadership competences in a lower-risk environment (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018).

Many college students are at a developmental stage where they “may form key motives, values, and aspects of identity that could shape their future actions and behaviors as leaders” (Waldman et al., 2012, p. 158). College is a time for personal exploration and growth, which includes learning their leadership identity (Komives et al., 2006). Just as students can be influenced toward professions through interaction with their professors or supervisors, students can also be influenced by those teaching leadership principles (Parks, 2005; Thompson, 2013).

One challenge with examining student affairs practitioners as leadership educators is that many never engaged in formal leadership studies coursework, as leadership education, formal or informal, is not a primary learning objective of student affairs preparatory programs (Dugan & Osteen, 2016). Student affairs practitioners tend to have advanced degrees in higher education administration or closely related fields and not leadership education/studies (Jenkins, 2012; Jenkins & Owen, 2016; O’Brien, 2018). Consequently, student affairs practitioners desiring to develop the leadership competency and capacity in their students must seek out professional development opportunities to gain the necessary leadership competencies they endeavor to teach students. Compounding the issue is the lack of a common list of competencies needed to be a leadership educator (Jenkins & Owen, 2016). Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore the leadership educator competencies needed by entry-level student affairs practitioners. This study was guided by the following research questions:

- How do student affairs practitioners/managers describe competence in leadership education for entry-level student affairs practitioners?

- How do student affairs preparatory program directors describe competence in leadership education for entry-level student affairs practitioners?

Literature Review

Leadership education encompasses both academic and student affairs (Buschlen & Guthrie, 2014; Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Hartman et al., 2015; Jenkins & Owen, 2016). Gone are the days when leadership education was only found in a formal classroom. Students now have extensive opportunities for leadership development housed within student affairs (Brungardt, 1996; Burns, 1995); the co-curricular context of leadership development. Although student affairs practitioners are considered leadership educators by experts in their field (Dunn et al., 2019), the professional preparation of student affairs leadership educators has not been well researched (Jenkins, 2012; Jenkins & Owen, 2016).

Before conducting an examination of leadership educators, it is important to distinguish between leadership development and leadership education. Leadership development is the broad umbrella term for an individual’s growth or advancement in their leadership capacity and competency throughout their life (Day, 2001). Leadership education falls under this umbrella and is the means through which individuals who are committed to and engaged in the leadership process learn, hone, and practice these leadership competencies over time (Guthrie & Jenkins, 2018; Northouse, 2019). Subsequently, the field of student affairs is recognized as an applied context for leadership education.

Framing leadership as process rather than position implies leadership can be learned as well as taught (Northouse, 2019; Roberts, 2007). However, what should leadership educators teach; as there is no universally accepted definition of leadership, nor is there agreement on the developmental process, the scaffolding of the curriculum, or where to house collegiate leadership programs (Rosch et al., 2017). Hartman et al. (2015) commented that unlike other disciplines, “there is little agreement on even the basic fundamentals” of leadership education (p. 455), which is “problematic because a template for appropriately scaffolding information does not exist” (p.456). Compounding the issue is the considerable breadth of what institutions and individuals consider a leadership program and the varied objectives associated with each (Rosch et al., 2017). Having limited experience with academic coursework in leadership studies and andragogy, leadership educators within student affairs can find it challenging to know which leadership competencies are essential and how to teach them effectively (Komives et al., 2011).

The concept of professional competencies is not new to student affairs (e.g. Burkard et al., 2005; Herdlein et al., 2010; Kuk et al., 2007; O’Brien, 2018), yet there is little consensus. Debate has occurred over how new professionals are prepared (Herdlein et al., 2013) and the required competencies for early career success (Cuyjet et al., 2009). Nevertheless, student affairs preparatory programs use competencies to measure a student’s proficiency prior to entering the profession (Dickerson et al., 2011; Jones & Voorhees, 2002; Kuk & Banning, 2009; O’Brien, 2018) and the productivity of the preparatory program (Hyman, 1988; Waple, 2006). Professional competencies “promote consistency and effectiveness among practitioners, especially those who enter the field from a variety of backgrounds” (O’Brien, 2018, p. 274).

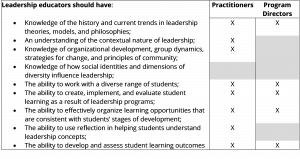

The most commonly recognized set of professional guidelines for student affairs comes from the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS). However, these are voluntary standards without quality control processes to ensure compliance. Moreover, the choices given to the programs to meet these standards do not ensure all graduates are “consistently gaining the knowledge and skills from preparation programs that are expected of them from student affairs administrators” (Kuk et al., 2007, p. 665). While Student Leadership Programs is one of the 45 specialty area standards published by CAS, the professional preparation, meaning the formal education and training as leadership educators, of those who direct or teach in such programs is not addressed (CAS, 2017). See Figure 1.

Figure 1

“Standards for Student Leadership Programs” suggested competencies for leadership educators (as cited in Jenkins & Owen, 2016)

The quality of preparation entry-level student affairs professionals receive in their master’s programs has been the focus of multiple studies (e.g. Burkard et al., 2005; Dickerson et al., 2011; Herdlein et al., 2010; Jones & Voorhees, 2002; Kuk & Banning, 2009; Kuk et al., 2007) and is vital for the maturation of a profession (Cuyjet et al., 2009). However, only limited consensus of the competencies needed by entry-level student affairs professionals has emerged (Herdlein et al., 2013; Waple, 2006). Master’s program faculty and student affairs practitioners tend to have significant differences in their perceptions of possession of competencies in entry-level student affairs practitioners (Kuk et al., 2007; Miles, 2007), the competencies needed to be successful as a student affairs practitioner (Hyman, 1985), where these competencies should be obtained (Kuk et al., 2007), and what should be taught (Herdlein et al., 2013).

The trend in competency research reached a peak in 2015, with the ACPA/NASPA taskforce to identify and categorize the competencies student affairs practitioners needed to be successful (Eanes et al., 2015; O’Brien, 2018). The result was a list of ten competencies ranging from technology to personal and ethical foundations. Leadership, in terms of being a positional leader within the organization, was included; however, leadership education and leadership educator professional preparation were not (Eanes et al., 2015).

Methods

A classic Delphi approach was used. This study, as part of a larger study, was conducted to stimulate and distill group opinions (Dalkey, 1969a; Delbecq et al., 1975; Franklin & Hart, 2007). A diverse group of qualified experts from across student affairs were purposively chosen as the panel of experts to elicit a wide range of opinions (Buriak & Shinn, 1989; Dalkey 1969a; Delbecq et al., 1975; Rayens & Hahn, 2000; Schmidt, 1997).

Population. To understand the preparation of entry-level student affairs leadership educators, one needs to consider both the academic and experiential perspectives (Herdlein et al., 2013; Kuk et al., 2007). Previous research has shown that student affairs practitioners and preparatory program faculty view the necessary competencies of student affairs practitioners differently (Hyman, 1985; Kuk et al., 2007; Miles, 2007). Consequently, two separate Delphi panels were conducted concurrently: Group A – Student Affairs Practitioners and Group B – Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors.

For most, their master’s coursework is the first scholarly exploration of student affairs as an academic field, thus preparatory program faculty are responsible for how pre-service practitioners view the theoretical and research basis of the profession (Herdlein et al.2013; Kuk et al., 2007). However, as Burkard et al. (2005) noted, “no one may be better positioned to help us understand the necessary entry-level competencies of a student affairs professional than those individuals who recruit, select, hire, and supervise such staff members” (p.286). While the findings of this study are focused on entry-level student affairs practitioners, they were excluded from the population as they do not always know, or may have an inflated sense of, the competencies needed to be successful in their chosen profession (Cuyjet et al., 2009).

Participants were purposively selected for each Delphi panel based on their experience or expertise in leadership education within student affairs (Delbecq et al., 1975; Linstone & Turoff, 1975; Rayens & Hahn, 2000). The depth of their experience was such that their opinions are seen as credible and representative (Delbecq et al., 1975; Franklin & Hart, 2007). A sampling frame was used for selection of each panel. Panelists needed to have demonstrated experience or expertise in (a) student affairs as a profession and (b) initiatives to foster the leadership development of college students. Expertise was determined as meeting at least three of the following criteria:

- Three or more years of experience as a full-time student affairs practitioner or researcher

- Three or more years of experience with college student leadership development

- Three or more years supervising entry-level student affairs practitioners

- Three or more years of experience as a preparatory student affairs program director/coordinator

- Three or more years teaching in a preparatory student affairs master’s program

Two Samples. A common belief is larger groups provide a more accurate representation of the voice or opinion of said group. However, Dalkey (1969b) determined that the opinion of large groups could accurately be represented with only 13 individuals, while also satisfactorily answering questions of process reliability. It was anticipated that not all participants would complete all rounds of the study, thus the target was to recruit a minimum of 17 participants per panel.

The search for potential participants began with an examination of the Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice and the Journal of College Student Development, between the years of 2008 and 2018. This search did not produce a large enough pool of student affairs professionals to establish a Delphi panel for either group. Subsequently, but within the aim to uphold the original intent of the study, five additional journals were examined (the Journal of Leadership Education, College Student Journal, NASPA Journal, College Student Affairs Journal, and Research and Practice in Assessment).

The search focused on articles related to necessary competencies for student affairs practitioners or leadership education in student affairs. Only the identified authors who met the participant criteria were invited to participate and were asked to nominate a student affairs colleague or student affairs preparatory program director who met the included selection criteria. Once each panel had 17-20 unique participants, invitations ceased.

Through this process, 32 student affairs practitioners were identified (Group A) and 17 agreed to participate. All were employed at public institutions and had varied experience within student affairs. Attrition in Group A occurred (from 17 to 13). Traditionally, a student affairs preparatory program is a two-year, residential master’s program with a required clinical paraprofessional practice. Fifty-seven directors of traditional student affairs programs were invited, but only 10 agreed to participate (Group B). Thus, the online ACPA membership roster was searched for additional directors of traditional programs, which yielded 10 more names. Both public and private institutions were represented. All 20 participants held a higher education/student affairs faculty appointment at the time of the study. Attrition in Group B also occurred (from 20 to 15). Participants are described only by the meeting of a pre-determined criteria of expertise, not through demographics (Dalkey, 1969b).

Instrumentation. Both panels were asked the same open-ended questions to maximize the range of responses; thereby increasing the prospect of producing the most important items (Schmidt, 1997). Three rounds were needed to reach item rating stabilization.

Round 1 – Opinion Collection. The initial survey was sent to both Groups A and B via email with a group-specific link to the online survey. Using content analysis techniques (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016), responses were analyzed individually for each panel. Within each panel, similar statements were combined, and compound statements were separated before all unique statements were added to the Round 2 instrument (Linstone & Turoff, 1975; Schmidt, 1997). The responses were not edited.

Round 2 – Rating the Opinions. A personalized link to the panel-specific Round 2 survey was emailed to each expert who completed round 1. Using a 5-point response scale with 1 = Not at all Important to 5 = Extremely Important, participants were asked to rate the level of importance they associated with each statement (Delbecq et al., 1975; Linstone & Turoff, 1975). At the end of each section, participants were given the opportunity to include other item(s) they believed important.

Round 3 – Developing Consensus. Frequency distributions were used to extract and hone the responses received from round 2 (Buriak & Shinn, 1989). In efforts to explore a wide variety of opinions, any statement where at least 50% of the participants (na ≥ 8; nb ≥ 7) responded ‘important’ (rating of 4) or ‘extremely important’ (rating of 5) were carried over to the group-specific instrument for round 3 (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004; Schmidt, 1997). The threshold of 50% was set a priori.

The personalized Round 3 surveys included each expert’s round 2 response, and the frequency distributions of the ‘important’ and ‘extremely important’ responses from the other panelists for each statement. Participants could change their response to ‘moderately important,’ ‘important,’ ‘extremely important,’ or keep it as is. Any additional items that emerged from round 2 were included at the end of the applicable section. Participants were asked to rate these new items using the same 5-point response scale as in round 2. A supermajority of 75% or greater (na ≥ 10; nb ≥ 12) expert agreement of an item being ‘important’ or ‘extremely important’ at the end of round 3 was the measure of consensus and was set a priori.

Research Approach and Analysis

A constructivist, interpretive, qualitative research design was used (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Data were gathered from participants and then analyzed to identify necessary competencies, using an inductive process. Frequencies and counts were used to help facilitate consensus within each panel while identifying the divergence of opinions between panels (Rayens & Hahn, 2000). Stability, or the lack of variance in attitudes or opinions of the Delphi experts, can be seen as a sign of consensus or congruence on an item (Crisp et al., 1997).

Findings

The research questions driving this study were, How do (1) student affairs practitioners and (2) preparatory program faculty describe competence in leadership education for entry-level student affairs practitioners? To address these questions, the following query was asked of all panelists: What leadership education knowledge, skills, abilities, and attributes are required for entry-level student affairs practitioners?

Group A: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers. Group A generated 93 unique items in round 1, which comprised the Round 2 survey. For readability and to reduce participant fatigue, the Round 2 survey was divided into component-specific blocks: knowledge (26 items), skills (32 items), and abilities/attributes (35 items). Twelve of the 13 Group A experts elected to change at least one of their round 2 scores. At the end of round 3, more than 85% of the responses (n = 789) were not changed from round 2. This stability in the data indicates a certain level of confidence in the experts’ responses. Of the 134 responses that were changed, 79.85% (n = 107), were changed to a higher level of importance; thereby reinforcing the initial importance associated with these items.

Table 1 details the required leadership educator knowledge responses for Group A. Items are organized in descending order of round 3 frequency counts. The summated ‘important’ and ‘extremely important’ responses for each item are detailed. Of the 26 knowledge items generated from round 1 and rated in round 2, 19 met the criteria to be forwarded to round 3. The seven items not forwarded are included in Table 2. Four ‘other’ knowledge items emerged in round 2 and were initially rated in round 3: knowledge of social justice, knowledge of when to be a follower, instructional strategies that expand curricular & co-curricular programs, and how students learn leadership. Of the 21 knowledge items rated in round 3, 17 were considered required for entry-level student affairs leadership educators, including two items generated from the ‘other’ responses. While familiarity with leadership theories and the leadership competency outlined in the ACPA/NASPA professional competencies were initially mentioned as necessary, both failed to reach the criteria for advancement to the third round of the study, and ultimately were not considered required knowledge for entry-level student affairs leadership educators.

| Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Knowledge: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14; Round 3, N= 13) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| Intentional program development | 100.0 (14) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Diversity and inclusion | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Self-understanding and understanding of others | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Experiential learning | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Community building | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| The theory of teams and group dynamics | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Student development theory | 78.6 (11) | 92.3 (12) | 7 (tied) |

| The leadership education desired at their institution | 78.6 (11) | 92.3 (12) | 7 (tied) |

| Social justice | Not rated | 92.3 (12) | 7 (tied) |

| The constructs of leader and leadership | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 10 (tied) |

| Core knowledge of ways to practice leadership | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 10 (tied) |

| Leadership identity development | 57.1 (8) | 84.6 (11) | 10 (tied) |

| When to be a follower | Not rated | 84.6 (11) | 10 (tied) |

| Trends in social issues | 78.6 (11) | 76.9 (10) | 14 (tied) |

| A willingness to explore leadership theories | 71.4 (10) | 76.9 (10) | 14 (tied) |

| Leadership instruments/assessments | 57.1 (8) | 76.9 (10) | 14 (tied) |

| Change agency and change process | 57.1 (8) | 76.9 (10) | 14 (tied) |

| Basic understanding of leadership theories* | 64.3 (9) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Where their own learning occurred* | 57.1 (8) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Not one single set of core knowledge needed* | 57.1 (8) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Campus-based information* | 71.4 (10) | 61.5 (8) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

| Table 2

Descriptive Statistics of Identified but Not Required Leadership Educator Knowledge: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14) |

|

| Item | Responses % (f) |

| Progression of leadership theory | 42.9 (6) |

| Familiarity with leadership competency of the ACPA/NASPA Professional Competencies | 35.7 (5) |

| Research on leadership development | 35.7 (5) |

| Knowledge of organizational management | 21.4 (3) |

| Knowledge of the social sector | 21.4 (3) |

| Knowledge of the history of higher education | 28.6 (4) |

| Knowledge of leadership competencies highlighted in Seemiller and Murray’s work | 28.6 (4) |

Table 3 details the required leadership educator skills for Group A and is organized likewise to Table 1. Of the 32 skill items generated in round 1, 26 met the criteria to advance to round 3. The six items not advanced are included in Table 4. No ‘other’ skills were identified in round 2. Twenty-one skills items met the criteria to be regarded as required for entry-level student affairs leadership educators. Considering the time entry-level student affairs leadership educators spend advising student organizations and meeting with students, it was surprising that managing meetings and effective supervision did not advance beyond round 2 (see Table 4). But it was not surprising that practical strategic planning did not advance through the Delphi process, as strategic planning typically is beyond the job responsibilities of entry-level employees.

| Table 3

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Skills: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14; Round 3, N= 13) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| Relationship building | 100.0 (14) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Counseling/listening/advising | 100.0 (14) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Self-awareness | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Awareness of others | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Cultural competencies | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Reflection | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Problem-solving | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Critical thinking | 92.9 (13) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Professionalism | 85.7 (12) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Effective oral and written communication | 85.7 (12) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Coaching | 71.4 (10) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Life-long learner | 85.7 (12) | 84.6 (11) | 12 (tied) |

| General leadership | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 12 (tied) |

| Communicate perspective of a situation & offer insight to action | 64.3 (9) | 84.6 (11) | 12 (tied) |

| Effective conflict negotiation | 78.6 (11) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Assessment practices | 78.6 (11) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Student advocacy | 71.4 (10) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Effective presentation and facilitation | 71.4 (10) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Project and event planning | 64.3 (9) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Mentoring | 64.3 (9) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Well-organized | 57.1 (8) | 76.9 (10) | 15 (tied) |

| Creative thinking* | 71.4 (10) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Administrative management* | 64.3 (9) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Time management* | 57.1 (8) | 61.5 (8) | |

| Effective teaching skills/strategies* | 57.1 (8) | 61.5 (8) | |

| Curriculum development* | 50.0 (7) | 61.5 (8) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

| Table 4

Descriptive Statistics of Identified but Not Required Leadership Educator Skills: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14) |

|

| Item | Responses % (f) |

| Meeting management | 42.9 (6) |

| There is not one set of core leadership education skills | 42.9 (6) |

| Objectively observe and summarize situations in need of intervention or organizational process in need of review | 42.9 (6) |

| Leading multi-generational teams | 35.7 (5) |

| Practical strategic planning | 35.7 (5) |

| Effective supervision | 28.6 (4) |

Table 5 details the required abilities or attributes of a student affairs leadership educator and is organized in like manner to Table 1. Thirty-five items were identified in round 1 and 26 were advanced to round 3. The nine items that were not advanced are listed in Table 6. Of interest is the stagnation of the item ‘ability to relate to novice leaders.’ No ‘other’ abilities/attributes items were identified in round 2.

| Table 5

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Abilities/Attributes: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14; Round 3, N= 13) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| Openness towards and inclusivity of all identities | 100.0 (14 ) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Communicate across differences | 100.0 (14 ) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Work on a team | 92.9 (13) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Be an ethical decision-maker | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Be a critical thinker | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Challenge students appropriately | 85.7 (12) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Help students and others dig deep | 71.4 (10) | 100.0 (13) | 1 (tied) |

| Carry out a plan beyond a single event or program | 92.9 (13) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Being a continuous learner | 92.9 (13) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Desire to learn | 85.7 (12) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Student empowerment and delegation | 85.7 (12) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Desire to teach students | 71.4 (10) | 92.3 (12) | 8 (tied) |

| Have difficult conversations | 85.7 (12) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Willingness to provide constructive feedback to students | 85.7 (12) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Set goals | 85.7 (12) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Work independently | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Patience | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Positive attitude | 78.6 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Create strategies mapped to learning outcomes | 71.4 (10) | 84.6 (11) | 13 (tied) |

| Focus on positive change | 78.6 (11) | 76.9 (10) | 20 (tied) |

| Hold people accountable | 71.4 (10) | 76.9 (10) | 20 (tied) |

| Help student identify ways to practice and find opportunities that will help them engage in challenge areas | 71.4 (10) | 76.9 (10) | 20 (tied) |

| Initiative * | 78.6 (11) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Loosely bound to student performance – you can’t force student to be better leaders, they have to do the work* | 57.1 (8) | 69.2 (9) | |

| Translate desired leadership education into learning outcomes for co-curricular learning* | 57.1 (8) | 53.8 (7) | |

| Creative and innovative spirit* | 57.1 (8) | 38.5 (5) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

| Table 6

Descriptive Statistics of Identified but Not Required Leadership Educator Abilities/Attributes: Student Affairs Practitioners/Managers (Round 2, N= 14) |

|

| Item | Responses % (f) |

| Relate to novice leaders | 42.9 (6) |

| Generate ideas/be creative | 42.9 (6) |

| Event planning experience | 35.7 (5) |

| There is not one set of core leadership education abilities or attributes | 35.7 (5) |

| Facilitate consensus | 35.7 (5) |

| Focus on youth development | 28.6 (4) |

| Develop a written long-term plan | 28.6 (4) |

| Communicate steps in a long-term plan to others | 21.4 (3) |

| Direct experience leading a group | 21.4 (3) |

Group B: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors. Group B experts generated 116 unique items in round 1, which were included in the Round 2 survey. Like the Round 2 survey for Group A, the Round 2 survey for Group B was divided into component-specific blocks: knowledge (33 items), skills (30 items), and abilities/attributes (53 items).

All but three of the Group B experts elected to change at least one of their round 2 scores. At the end of round 3, over 86% of the responses (n = 1,296) were not changed from round 2. This limited change shows a level of confidence in the participants’ responses. Of the 204 responses that were changed, 89.22% (n = 182) were changed to a higher level of importance; reinforcing the initial importance the participants associated with these items.

Table 7 details the required leadership educator knowledge responses for Group B and is similarly organized to Table 1. Of the 33 knowledge items, 25 met the criteria to be advanced to round 3. The eight remaining items are included in Table 8. Four ‘other’ knowledge items emerged from round 2 and were initially rated in round 3. At the end of round 3, 22 knowledge items were considered required for entry-level student affairs leadership educators, including one ‘other’ response from round 2.

| Table 7

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Knowledge: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors (Round 2, N= 16; Round 3, N= 15) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| When to refer a student to other campus resources | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Theoretical underpinning of student development theory | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Theoretical understanding of college environments & organizations | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Practical and conceptual understanding of the college experience and different pathways thereof | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Diverse student subpopulations throughout higher education at large | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Deep understanding of diversity, inclusion, privilege, oppression, & power dynamics | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Ethical standards | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Research about college students | 87.5 (14) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| How identity plays into the experience of college for diverse subgroups | 93.8 (15) | 93.3 (14) | 9 (tied) |

| Diverse student subpopulations within specific institution | 87.5 (14) | 93.3 (14) | 9 (tied) |

| Social justice | 81.3 (13) | 93.3 (14) | 9 (tied) |

| Basic understanding of leadership theory | 75.0 (12) | 93.3 (14) | 9 (tied) |

| How to accept feedback and make behavioral modifications | Not rated | 93.3 (14) | 9 (tied) |

| Self | 93.8 (15) | 86.7 (13) | 14 (tied) |

| Program evaluation and assessment | 81.3 (13) | 86.7 (13) | 14 (tied) |

| Higher education governance | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 14 (tied) |

| How to infuse practice with theory | 81.3 (13) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| Group dynamics | 81.3 (13) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| One’s role within the institution | 75.0 (12) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| The political campus environment and how to navigate it | 75.0 (12) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| The fundamentals of higher education law | 62.5 (10) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| The history of US higher education | 56.3 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 17 (tied) |

| That leadership does not require a position/title* | 56.3 (9) | 73.3 (11) | |

| The emergence and growth of student affairs as a profession* | 50.0 (8) | 73.3 (11) | |

| The important role of context in leadership development & education* | 56.3 (9) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Deep understanding of inner workings of a particular functional area* | 50.0 (8) | 46.7 (7) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

| Table 8

Descriptive Statistics of Identified but Not Required Leadership Educator Knowledge: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors (Round 2, N= 16) |

|

| Item | Responses % (f) |

| Understanding of enrollment trends | 43.8 (7) |

| Knowledge of ACPA/NASPA professional competency in leadership | 43.8 (7) |

| Knowledge of the ACPA/NASPA professional competencies in general | 43.8 (7) |

| Understanding of development as an avenue to impact positive change | 43.8 (7) |

| Understanding team motivation | 43.8 (7) |

| An understanding of at least the Social Change Model of leadership | 37.5 (6) |

| Deep understanding of multiple functional areas | 31.3 (5) |

| Knowledge of the evolution of leadership theory | 18.8 (3) |

The required leadership educator skills responses for Group B are described in Table 9, again formatted to Table 1. All 30 skill items generated from round 1 met the advancement criteria for round 3. Creativity was identified in round 2 as an additional skill and included in round 3 for initial rating, but was not considered a required skill. Of the 30 skills initially named, 21 met the criteria to be considered required for entry-level student affairs leadership educators.

| Table 9

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Skills: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors (Round 2, N= 16; Round 3, N= 15) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| Problem solving | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Listening | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Critical thinking | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Effectively work with diverse individuals | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Effective oral & written communication | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Interpersonal | 87.5 (14) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Effectively working with teams | 87.5 (14) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Effective self-reflection | 75.0 (12) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Group facilitation | 75.0 (12) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Create and sustain healthy environments | 87.5 (14) | 93.3 (14) | 10 (tied) |

| Build programs to meet desired outcomes | 75.0 (12) | 93.3 (14) | 10 (tied) |

| Organization | 87.5 (14) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Public speaking | 81.3 (13) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Running an effective meeting | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Learn the culture of the office | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Excellent time management | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Crisis/emergency management | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Basic research/assessment | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 12 (tied) |

| Conflict resolution/management | 75.0 (12) | 80.0 (12) | 19 (tied) |

| Restorative practices | 56.3 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 19 (tied) |

| Establish a strong vision for a group | 56.3 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 19 (tied) |

| Resilience* | 75.0 (12) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Effective dialogue* | 62.5 (10) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Advising student organizations* | 62.5 (10) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Counseling* | 62.5 (10) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Delegation* | 62.5 (10) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Event/program planning* | 56.3 (9) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Enhancing group morale* | 62.5 (10) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Supervision* | 62.5 (10) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Entrepreneurial thinking with an eye towards innovation* | 56.3 (9) | 60.0 (9) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

Table 10, organized to Table 1, details the required abilities or attributes of a student affairs leadership educator as identified by Group B. Fifty-three ability/attribute items were named in round 1 and 45 met the criteria to advance to round 3. The eight items that did not meet the advancement criteria are listed in Table 11. Group B experts did not find the possession of strong personal values nor the ability to help students become active citizens in their community to be required abilities or attributes of effective leadership educators. One ‘other’ item, incorporation of service-learning, was identified in round 2 and rated in round 3 but was not found to be a required ability.

| Table 10

Descriptive Statistics of Required Leadership Educator Abilities/Attributes: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors (Round 2, N= 16; Round 3, N= 15) |

|||

| Responses % (f) | |||

| Item | Round 2 | Round 3 | Rank Order |

| Learn from mistakes | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Respect for all students | 100.0 (16) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Trustworthiness | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Multicultural competence | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Willing to learn/grow | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Develop leadership capacity in diverse students in/out of the classroom | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Flexibility or adaptability | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Committed to equity and inclusion | 93.8 (15) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Analyze situations | 81.3 (13) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Foresee possible outcomes of decisions/actions | 68.8 (11) | 100.0 (15) | 1 (tied) |

| Sensitivity to the needs and experiences of individuals & diverse subpopulations | 93.8 (15) | 93.3 (14) | 11 (tied) |

| Willing to mentor and be mentored | 87.5 (14) | 93.3 (14) | 11 (tied) |

| Hard working | 87.5 (14) | 93.3 (14) | 13 (tied) |

| Enjoys working with students | 81.3 (13) | 93.3 (14) | 13 (tied) |

| Persistence to help students recognize and internalize mistakes, good decisions, missed opportunities, and to celebrate achievements | 81.3 (13) | 93.3 (14) | 13 (tied) |

| Willing to challenge and question others | 75.0 (12) | 93.3 (14) | 13 (tied) |

| Authenticity | 75.0 (12) | 93.3 (14) | 13 (tied) |

| Support those with whom personal values and beliefs may differ | 93.8 (15) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Willing to be challenged and questioned | 81.3 (13) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Developed sense of responsibility | 81.3 (13) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Compassion | 81.3 (13) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Articulate the importance of student affairs and its impact on student success, engagement, learning, and development | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Understanding one’s own needs | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Ask clarifying questions | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Build community | 75.0 (12) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Patience | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Understand and support institutional policy | 68.8 (11) | 86.7 (13) | 18 (tied) |

| Empathetic | 62.5 (10) | 86.7 (13) | 28 (tied) |

| Motivation/being a self-starter | 75.0 (12) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Insight into ways actual college experiences deviate from theoretical | 68.8 (11) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Desire to contribute to a better world | 68.8 (11) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Self-confidence | 68.8 (11) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Mediate and bring groups to consensus | 68.8 (11) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Effectively communicate with multiple stakeholders | 62.5 (10) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Articulate leadership experiences and skills may impact students | 62.5 (10) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Develop others | 62.5 (10) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Have vision for the “big picture” | 56.3 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Communicate conceptual ideas through practical lens | 56.3 (9) | 80.0 (12) | 28 (tied) |

| Can articulate the importance of college for students* | 75.0 (12) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Develop alternative pathways when advising students* | 68.8 (11) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Respond to broad-based constituencies and issues* | 50.0 (8) | 73.3 (11) | |

| Conscious choice-making* | 56.3 (9) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Build effective teams* | 56.3 (9) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Think outside the box* | 56.3 (9) | 66.7 (10) | |

| Calculated risk-taking* | 50.0 (8) | 60.0 (9) | |

* Item did not meet the 75% supermajority at the end of round 3 and was not considered in final ranking

| Table 11

Descriptive Statistics of Identified but Not Required Leadership Educator Abilities/Attributes: Student Affairs Preparatory Program Directors (Round 2, N= 16) |

|

| Item | Responses % (f) |

| Strong personal values | 43.8 (7) |

| Political acumen/political savvy | 43.8 (7) |

| Patience to observe “failure” | 43.8 (7) |

| Capacity to negotiate | 37.5 (6) |

| Being able to envision, plan, and affect change in an organization | 31.3 (5) |

| Help others become active citizens in their community | 31.3 (5) |

| Charismatic (but not necessarily extroverted) | 12.5 (2) |

| Capacity to persuade, argue, and debate | 12.5 (2) |

Conclusions

The lists of the required leadership educator competencies for entry-level student affairs leadership educators generated by the two Delphi panels were fairly distinctive. This finding is consistent with previous research that student affairs practitioners and student affairs preparatory program faculty disagree on the competencies needed to be a successful student affairs practitioner (Hyman, 1985; Kuk et al., 2007; Miles, 2007). In total, 141 competencies were identified, 60 for Group A and 81 for Group B, but only 13 (9.22%) were duplicated between the two panels (Table 12). The most duplication came in the skills list, with seven of the 42 items (16.7%) repeated. Only one of the 141 identified competencies, ‘openness towards and inclusivity of all identities’ had a consensus rating in every round, as Group B experts repeatedly and unanimously identified it ‘extremely important.’

| Table 12

Leadership Educator Competencies Identified as Required by Both Delphi Groups

|

||

| Knowledge | Skills | Abilities/Attributes |

| Self-understanding | Reflection | Challenge Students Appropriately |

| Team and Group Dynamics | Problem-solving | Being a Continuous Learner |

| Social Justice | Listening | Patience |

| Effective Oral and Written Communication | ||

| Critical thinking | ||

| Effective Conflict Negotiation/Management | ||

| Organization | ||

The lack of duplication was also seen within the competencies identified by each panel. Only three of the 60 competencies (5%) identified by Group A were repeated: ‘change process’ (knowledge and abilities/attributes), ‘self-awareness’, and ‘awareness of others’ (both knowledge and skills). For Group B, none of the 81 competencies identified were repeated.

One potential reason for the divergence between the panels is that each appears to have responded with items analogous to their respective duties within the institution. Student Affairs practitioners tend to work with a wide array of students who have an equally wide range of leadership experience and competency. Thus, it is appropriate that they identified more practical, hands-on competencies and best practices applicable, regardless of functional area, to a broad audience with varying levels of leadership proficiency. Moreover, the lack of familiarity with the theoretical or conceptual aspects of leadership education could have influenced their responses.

However, the stagnation of the ‘ability to work with novice leaders’ raises additional questions. If student affairs practitioners routinely work with students with varying levels of leadership experience and competency, it follows that the ability to relate to novice leaders would be important. Thus, it begs the question, do practitioners believe novice leaders have no place in student affairs leadership initiatives or do they believe the students engaging in student affairs leadership initiatives should not be considered novice leaders?

In contrast, Group B experts identified more conceptually focused competencies. A significant portion of a faculty member’s job is the dissemination of knowledge. Thus, it was expected that the Group B experts identified competencies with a more conceptual leaning. Likewise, the general applicability of the identified competencies to any student affairs practitioner was not surprising, as student affairs preparatory program faculty are responsible for training student affairs generalists, not functional area experts. But the lack of leadership theory and practice concepts identified by Group B was unexpected, especially since preparatory program faculty members consider entry-level student affairs practitioners to be leadership educators (Dunn et al., 2019). Only 12 of the 81 competencies (14.8%) can be directly connected to leadership education.

Data reduction is a prominent component of the Delphi technique, so the final results are only as good as the original data. Subsequently, the lead researcher returned to the initial data provided by Group B (Tables 7 to 11) to determine if items more closely connected to leadership education principles were identified initially but were deemed less important. In terms of required knowledge (Table 8) several items closely related to leadership education were proposed but none met the criteria for advancement. In fact, the item Group B found least important was ‘knowledge of the evolution of leadership theory.’ Two of the new items proposed in round 2, ‘personal definitions of leadership’ and ‘relational aspects of leader-follower relationships or opportunities,’ were clearly connected to leadership education theory and practice. Yet, neither item met the criteria to be forwarded to the next round. All skill items from round 2 were advanced to round 3 (Table 9), so the lack of leadership education specific skills at the end is a direct result of not having any at the beginning. The original abilities/attributes items include three closely related to leadership education, but again none met the criteria to be advanced to the next round (Table 11).

CAS proposed nine professional standards for the student affairs practitioners who oversee co-curricular leadership programs (Figure 1). Five standards were identified by both panels, with Group A identifying three additional standards for a total of eight. However, one professional competency was not included in either expert panel list – understanding how social identity influences one’s leadership (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Comparisons of Delphi group results to the “Standards for Student Leadership Programs” suggested competencies for leadership educators (as cited in Jenkins & Owen, 2016)

| Leadership educators should have:

|

Practitioners | Program Directors |

| · Knowledge of the history and current trends in leadership theories, models, and philosophies; | X | X |

| · An understanding of the contextual nature of leadership; | X | |

| · Knowledge of organizational development, group dynamics, strategies for change, and principles of community; | X | |

| · Knowledge of how social identities and dimensions of diversity influence leadership; | ||

| · The ability to work with a diverse range of students; | X | X |

| · The ability to create, implement, and evaluate student learning as a result of leadership programs; | X | X |

| · The ability to effectively organize learning opportunities that are consistent with students’ stages of development; | X | X |

| · The ability to use reflection in helping students understand leadership concepts; | X | |

| · The ability to develop and assess student learning outcomes | X | X |

Unexpectedly, Group B experts included just over half of the CAS professional standards. These individuals are student affairs content and context experts, whose primary job is to teach and train the next generation of student affairs practitioners and researchers, but they did not include many of the standards by which the profession is measured. The fact that CAS was not mentioned by the student affairs faculty panel in any of the rounds of data collection (see Tables 7 to 11), and then only half of the competencies were identified individually without a connection to their association with CAS at the end of the study, begs the question: is CAS and its professional standards still relevant today when it comes to leadership education in the student affairs context?

However, student affairs practitioners still find CAS relevant. Unlike their counterparts, Group A experts listed eight of the nine competencies identified by CAS from the very beginning of the study. This result shows a disconnect between the two panels. If the student affairs faculty experts do not immediately think of the professional competencies promoted by CAS, then where and how did the practitioners become familiar enough with them that eight of the nine professional competencies readily came to mind when asked the original question?

Recommendations

This study confirmed previous research that student affairs practitioners and faculty members do not always agree on what professional competencies are needed to be a successful student affairs professional and expanded the discussion of professional competencies into the area of leadership educator professional preparation. While their differences are understandable, this disagreement contributes to the on-going gap between theory and practice within co-curricular leadership education. In efforts to help bridge this gap, four recommendations are presented.

First, increased communication is needed. Not only between student affairs practitioners who supervise graduate students and preparatory program faculty, but also between the graduate students and their supervisors and faculty members. If learning in and out of the classroom is to be reinforced, more meaningful partnerships between those whose primary role is to facilitate that learning must be created. Moreover, the role student affairs practitioners play as leadership educators needs to be clearly articulated to those enrolled in the preparatory programs, regardless of desired functional area after graduation. They need to understand professional expectations prior to entering the profession full-time, in order to take advantage of educational or other development opportunities to fill any perceived gaps prior to graduation.

Second, we recommend that leadership studies faculty and student affairs practioners work to build more intentional partnerships. Having leadership education scholars and student affairs practitioners working collaboratively, in both research and leadership education initiatives, such as formal classes, trainings, or other professional development offerings, provides opportunities to learn from each other and advance both fields. These partnerships can also strengthen the leadership education and training of pre-service student affairs leadership educators, as well as current student affairs practitioners, which in turn can strengthen and reinforce the leadership education happening in both curricular and co-curricular spaces.

Third, while this study examined the leadership educator competencies required for entry-level student affairs practitioners, expanding the study to include student affairs practitioners at multiple career levels could be useful. Previous research shows that an individual’s role or professional position within student affairs influences the perceived relevance of and demonstrated proficiency in professional competencies in general (Herdlein et al., 2013). It could be useful to examine if this trend also holds for leadership educator competencies as an individual advances within the organization, which could inform professional development and continuing education programming content for all student affairs practitioners.

Fourth, we recommend exploring the relationship between social identities and how leadership is both taught and demonstrated. As neither expert panel identified an understanding of the relationship between social identity and leadership as a required competency for entry-level student affairs leadership educators, but CAS identified it as one of the nine competencies for those who manage/coordinate leadership programs, there is a gap that needs to be explored. This gap also raises other questions, such as: Do the espoused social identities of the leadership educator influence how they teach and train others to be effective leaders? And is there a professional leadership educator identity for student affairs leadership educators? Additional research is needed.

References

Brungardt, C. (1996). The making of leaders: A review of the research in leadership development and education. The Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(3), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179199700300309

Buriak, P., & Shinn, G. C. (1989). Mission, initiatives, and obstacles to research in agricultural education: A national Delphi using external decision-makers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 30(4), 14-23. http://www.jae-online.org/attachments/article/845/Buriak,%20P%20&%20Shinn,%20G_Vol30_4_14-23.pdf

Burkard, A. W., Cole, D. C., Ott, M., & Stoflet, T. (2005). Entry-level competencies of new student affairs professionals: A Delphi study. NASPA Journal, 42(3), 283-309.

Burns, J. S. (1995). Leadership studies: A new partnership between academic departments and student affairs. NASPA Journal, 32(4), 242-250.

Buschlen, E., & Guthrie, K. L. (2014). Seamless leadership learning in curricular and cocurricular facets of university life: A pragmatic approach to praxis. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(4), 58-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.2131

Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS) (2017). Standards. http://www.cas.edu/standards

Crisp, J. Pelleteir, D., Duffield, C., Adams, A., & Nagy, S. (1997). The Delphi method? Nursing Research, 46, 116-118.

Cuyjet, M. J., Longwell-Grice, R., & Molina, E. (2009). Perceptions of new student affairs professionals and their supervisors regarding the application of competencies learned in preparation programs. Journal of College Student Development, 50(1), 104-119. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/258119

Dalkey, N. C. (1969a). An experimental study of group opinion: The Delphi method. Futures, 1(5), 408-426.

Dalkey, N. C. (1969b). The Delphi method: An experimental study of group opinion. The Rand Corporation.

Day, D. V. (2001). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581-613.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Scott, Foreman and Company.

Dickerson, A. M., Hoffman, J. L., Anan, B. P., Brown, K. F., Vong, L. K., Bresciani, M. J., Monzon, R., & Oyler, J. (2011). A comparison of senior student affairs officer and student affairs preparatory program faculty expectations of entry-level professionals’ competencies. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 48(4), 463-479. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.6270

Dugan, J. P., & Osteen, L. (2016). Leadership. In J. H. Schuh, S. R. Jones, & V. Torres (Eds). Student services: A handbook for the profession (6th ed.) (pp. 408-422). Jossey-Bass.

Dunn, A. L., Moore, L. L., Odom, S. F., Bailey, K. J., & Briers, G. E. (2019). Leadership education beyond the classroom: Characteristics of student affairs leadership educators. Journal of Leadership Education. 18(4), 94-113. https://journalofleadershiped.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/18_4_Dunn1v2.pdf

Eanes, B. J., Perrillo, P. A., Fechter, T., Gordon, S. A., Harper, S., Havice, P., Hoffman, J. L., Martin III, Q., Osteen, L., Pina, J. B., Simpkins, W., Tran, V. T., Kelly, B. T., & Willoughby, C. (2015). Professional competency areas for student affairs educators. https://www.naspa.org/images/uploads/main/ACPA_NASPA_Professional_Competencies_FINAL.pdf

Franklin, K. K., & Hart, J. K. (2007). Idea generation and exploration: Benefits and limitations of the policy Delphi research method. Innovative Higher Education, 31, 237-246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-006-9022-8

Guthrie, K., & Jenkins, D. M. (2018). The role of leadership educators: Transforming learning. Information Age Publishing.

Hartman, N. S., Allen, S. J., & Miguel, R. F. (2015). An exploration of teaching methods used to develop leaders: Leadership educator’s perspectives. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, 36(5), 454-472, https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2013-0097

Herdlein, R., Kline, K., Boquard, B., & Haddad, V. (2010). A survey of faculty perceptions of learning outcomes in master’s level programs in higher education and student affairs. College Student Affairs Journal, 29(1), 33-45.

Herdlein, R., Riefler, L., & Mrowka, K. (2013). An integrative literature review of student affairs competencies: A meta-analysis. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 50(3), 250-269. https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2013-0019

Hyman, R. E. (1985, April). Do graduate preparation programs address competencies important to student affairs practice? Paper presented at the annual conference of the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators. Portland, OR.

Hyman, R. E. (1988). Graduate preparation for professional practice: A difference of perceptions. NASPA Journal, 26(2), 143-150.

Jenkins, D. M. (2012). Exploring signature pedagogies in undergraduate leadership education. Journal of Leadership Education, 11(1), 1-27.

Jenkins, D. M., & Owen, J. E. (2016). Who teaches leadership? A comparative analysis of faculty and student affairs leadership educators and implications for leadership learning. Journal of Leadership Education, 15(2), 98-113, https://journalofleadershiped.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/15_2_jenkins.pdf

Jones, E. A., & Voorhees, R. A. (2002). Defining and assessing learning: Exploring competency-based initiatives (NCES 2002-159). U.S. Department of Education.

Keating, K., Rosch, D., & Burgoon, L. (2014). Development readiness for leadership: the Differential effects of leadership courses on creating “ready, willing, and able” learners. Journal of Leadership Education, 13(3), 1-16. https://journalofleadershiped.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/13_3_keating117.pdf

Komives, S. R., Dugan, J. P., Owen, J. E. Slack, C., & Wagner, W. (2011). The handbook for student leadership development. Jossey-Bass.

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S. D., Owen, J. E., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2006). A leadership identity development model: Applications from a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0048

Kuk, L., & Banning, J. (2009). Student affairs preparation programs: A competency based approach to assessment and outcomes. College Student Journal, 43(2), 492-502.

Kuk, L., Cobb, B., & Forrest, C. (2007). Perceptions of competencies of entry-level practitioners in student affairs. NASPA Journal, 44(4), 664-691. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.1863

Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (1975). The Delphi method: Techniques and applications. Addison-Wesley Publishing.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Miles, J. M. (2007). Student affairs programs. In D. Wright, & M. T. Miller (Eds.). Training higher education policy makers and leaders (pp. 45-51). Information Age Publishing.

Northouse, P. (2019). Leadership theory and practice (8th ed.). Sage.

O’Brien, J. J. (2018). Exploring intersections among the ACPA/NASPA professional competencies. Journal of College Student Development, 59(3), 274-290. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0027

Okoli, C., & Pawlowski, S. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design consideration and application. Information & Management, 42, 15-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

Parks, S. D. (2005). Leadership can be taught: A bold approach for a complex world. Harvard Business School Press.

Rayens, M. K., & Hahn, E. J. (2000). Building consensus using the policy Delphi method. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 1(4), 308-315.

Roberts, D. C. (2007). Deeper learning in leadership: Helping college students find the potential within. Jossey-Bass.

Rosch, D. M., Collier, D., & Thompson, S. E. (2015). An exploration of students’ motivation to lead: An analysis by race, gender, and student leadership behaviors. Journal of College Student Development, 56(3), 286-291.

Rosch, D. M., Spencer, G. L., & Hoag, B. L. (2017). A comprehensive multi-level model for campus-based leadership education. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(4), 124-134. https://journalofleadershiped.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/16_4_rosch.pdf

Schmidt, R. C. (1997). Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decision Sciences, 28(3), 763-774.

Thompson, M. D. (2013). Student leadership development and orientation: Contributing resources within the liberal arts. American Journal of Education Research, 1(1), 1-6.

Waldman, D. A., Galvin, B. M., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2012). The development of motivation to lead and leader role identity. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(2), 156-168.

Waple, J. N. (2006). An assessment of skills and competencies necessary for entry-level student affairs work. NASPA Journal, 43(1), 1-18.