Introduction

The international student enrollment rate has been on the rise since the 1950s (Walker, 2000). More than 886,052 international students were enrolled at a college or university in the United States for the 2013-2014 academic year, which is an 8.1% growth compared to the previous academic year (Institute of International Education, 2014). Higher education institutions in the U.S. draw thousands of students because of their perceived quality and prestige (Bourke, 2000). Students choose to study in the U.S. for the quality of the institutions, the potential career opportunities a U.S. college degree can offer, a desire to enhance their English-speaking skills, and for the resources available to students (Bourke, 2000).

As the number of international students choosing to study at institutions in the U.S. continues to grow, there is a need to better understand those students’ experiences on campus (Harik-Williams, 2003). While many studies on international students focus on students’ transition to their host institutions and adapting to change, research on their involvement experience on campus is lacking (Arthur, 2004; Lee & Rice, 2007; Mamiseishvili 2012; Mori, 2000). By researching the involvement experiences of international students, institutions can identify the impact of involvement on international students, behaviors that increase student satisfaction, and ways international students contribute to the globalization of the campus environment. Furthermore, describing the lived experiences of international students who are involved will add to the body of literature on the impact of involvement on student development and success.

While research has linked undergraduate student satisfaction, retention, and academic success to involvement, there are few studies that have explored graduate student involvement (Farley, McKee, & Brooks, 2011). Questions around the level of impact involvement has on graduate students have mostly been left unanswered. Additionally, little is known about the impact of involvement on international graduate students (Harik-Williams, 2003). Harik- Williams (2003) posited that international students are underserved and do not receive proper support from their institutions. Although international student enrollment has been on the rise for decades, the literature offers little to the in-depth understanding of the international student experience. Moreover, research has shown international student adjustment is comparable to that of domestic students of color (Harik-Williams, 2003). Given the need to better support international students and the gaps in the literature, the purpose of this study was to describe the experience of international graduate students who were in a formal leadership role during their graduate studies.

Students who served in leadership roles were selected because that involvement experience meets many of Astin’s (1993) attributes of student engagement. Students in leadership roles were assumed to have an involvement experience that is continuous, requires an investment of time, and involves both qualitative and quantitative features. A qualitative methodology was used to obtain an in-depth understanding and capture the essence of international graduate students’ leadership experiences. The study was designed to provide insight into the lived leadership experiences of international graduate students at a U.S. based university. In addition, this study aimed to describe how international graduate students perceive their roles as leaders in a foreign cultural context. The findings of this study will fill gaps in the literature and provide recommendations for professionals who work with international students. This study is guided by one broad research question:

- What is the shared leadership experience of international graduate students in the United States?

Literature Review

This study describes the lived leadership experiences of international graduate students.

Graduate student leadership is defined as students who hold a formal role in a student organization; they served on the organizations’ executive board. This literature review provides a short summary of previous research on international students, and student involvement.

International Students. Students from around the world are traveling to the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States for a college degree in record numbers (Institute of International Education, 2014). In 1954, less than 35,000 international students were enrolled in a higher education institution in the United States (Walker, 2000). By the early 2000s, that figure was more than 20 times higher (Institute of International Education, 2014). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2014) predicted the rate of enrollment will more than double by the year 2020. There has especially been an increase in enrollment among students from Asia. Specifically, students from China, India, and South Korea are choosing to study in the United States at a much higher rate than students from other countries.

Huntley (1993) noted an increase in the number of Asian, female, and graduate international students enrolling in U.S. institutions. By the start of the 21st century, Asian students comprised 57.7% of the international student population in the U.S. and continued to be the largest group on campuses across the country (Institute of International Education, 2014).

While the growth in enrollment has its benefits, it also comes with considerable challenges. International students add to the diversity on campus and broadly enhance the globalization of the domestic student experience. Domestic students and international students benefit from high enrollment rates because both groups can develop critical skills to better engage in an increasingly global society when studying together. In addition, the institutions and host countries benefit economically from international student enrollment (Schweitzer, Morson,

& Mather, 2011). Students who studied in the U.S. added more than $27 billion to economy in 2014. However, many international students experience hardships during their transition in the

U.S. (Schweitzer et al., 2011). Thus, as colleges continue to host international students, understanding and addressing the needs to international students is essential.

The literature on international students has primarily focused on challenges students face when transiting to the U.S. education system. Studies have examined how international students navigate differences in cultural and social norms, connect and build friendships, and cope with isolation and loneliness (Gareis, 2012; Mori, 2000; Smith, 2016; Smith, & Demjanenko, 2011). Other researchers have given attention to issues affecting the quality of students’ experiences, such as academic stress, experiencing discrimination, financial strains, and English fluency (Arthur, 2004; Lee & Rice, 2007; Mamiseishvili 2012; Schweitzer et al., 2011). Given the current trends, scholars stress the importance of attending to the needs of international students (Smith, 2016). Smith (2016) posits student involvement can be strategy used to address many of the factors that hinder international students from adjusting to campus life in the United States.

Student Involvement. Although studies on student involvement have primarily focused on the undergraduate student experience, there are reasons to believe it can have similar impact on graduate students (Astin, 1993; Gardner and Barnes, 2007; Tinto 1993). The findings consistently show a positive relationship between involvement and student development, as well as with satisfaction and retention (Astin, 1993; Moore, Lovell, McGann, & Wyrick, 1998; Tinto 1993). Students who are involved in extracurricular activities are more likely to have stronger social ties on campus, network, discover their passion, experience personal growth, and perform well academically (Astin, 1993; Moore et al., 1998; Tinto, 1993). Given the outcomes of involvement for undergraduate students, Farley et al. (2011) examined the influence it has on graduate students.

There have been few empirical studies on the impact of involvement on graduate students (Farley et al., 2011). Gardner and Barnes (2007) conducted long interviews with 10 students in higher education doctoral programs. The authors found involvement had positive outcomes for students, such as: networking, engagement in the academic community, and professional development. The participants also indicated graduate student involvement is drastically different compared to undergraduate student involvement. For graduate students, involvement is primarily a part of the career planning process. The lack of graduate student visibility in the literature, arguably, mirrors colleges’ minimal efforts to support and engage graduate students on campus (Farley et al., 2011). This is particularly concerning when most international students studying in the U.S. are completing graduate degrees (Huntley, 1993, Institute of International Education, 2014). Furthermore, it is clear there are benefits to involvement for both undergraduate and graduate students (Astin, 1993; Gardner and Barnes, 2007; Huntley, 1993). Additional examination is needed to understand the level of impact involvement has on graduate students, specifically international graduate students (Farley et al., 2011; Harik-Williams, 2003).

International Student Involvement. While American undergraduate students in the U.S. are in a culture that stresses student involvement and leadership, international students are coming from varying cultural experiences (Harik-Williams, 2003; House and GLOBE, 2004). Moores and Popadiuk (2011) were among the first to publish on positive facets of international student adjustment in the literature; they found extracurricular activities have a positive impact on student experience. This finding is consistent with the literature on student involvement and satisfaction (Astin, 1993). Studies have shown there is a positive relationship between international student involvement on campus and overall college success (Abe, Talbot, & Geelhoed, 1998; Toyokawa & Toyokawa, 2002; Yoh & Pedersen, 2006). Although there are clear findings that suggest a positive relationship between involvement and student satisfaction, studies have not explored international students’ leadership experiences with involvement (Astin, 1993; Moore et al., 1998; Tinto 1993). Additionally, other scholars have identified several factors that affect international student satisfaction.

Yoh and Pedersen (2006) found academic satisfaction is linked to international students’ connection with U.S. peers, spoken English proficiency, and perception of discrimination. Social satisfaction is related to marital status, spoken English proficiency, perception of discrimination, and connection with U.S. peers. Satisfaction with the collegiate experience has no relationship to students’ career goals, sex, finances, and grades (Yoh & Pedersen, 2006). Moreover, international students’ experiences can also be influenced by their country of origin or ethnicity. Asian students tend to have more difficulties adjusting to campus life than non-Asian students (Abe et al., 1998). Toyokawa and Toyokawa (2002) examined the connection between Japanese students’ involvement in campus activities and adaption to U.S. campus life; they discovered student engagement is positively related to overall student success.

Summary of Literature Review. International student enrollment has been on the rise for decades, and shows no signs of slowing down (Institute of International Education, 2004). However, studies have shown international students are not getting the support they need to feel connected on their campus (Harik-Williams, 2003; Smith, 2016). While student involvement has been shown to increase overall student satisfaction, many of the studies have only focused on undergraduate students (Farley et al., 2011). This is problematic for many reasons, but one critical reason is that most international students are enrolled in graduate degree programs (Institute of International Education, 2014). Serving international graduate students require an understanding of the factors that influence their involvement and experience on campus (Farley et al., Smith, 2016).

Involvement is a viable strategy that can be used to enhance students’ experiences. Previous studies suggest any positive involvement and connection to the college campus can have a significant impact on international students’ satisfaction (Abe et al. 1998; Gardner & Barnes, 2007). Previous research also revealed a positive relationship between student engagement on campus and successful transition. Abe et al. (1998) found international students involved in a peer program were more likely to adjust socially than those students who did not participate in the program. Though the literature offers some support for the role of involvement in international graduate student’s satisfaction, there is little empirical support to validate the level of impact involvement has. Furthermore, for students who are involved in roles that are continuous and requires physical and psychological energy, little is known about the impact of their involvement. This study aims to address this question by conducting an in-depth examination of the lived leadership experience of international graduate students.

Conceptual Orientation

In addition to understanding the value of student involvement and international student trends in the U.S., it is important to explore how culture, student development, and leadership theory fit. Students come from different social norms and cultures. In this present study, research on leadership, culture, and student development are used to illuminate the lived leadership experiences of international graduate students in terms of their conceptualization of leadership, as well as their experience with involvement and leadership in the U.S.

Hall (1976) identified two dimensions of culture. Cultural characteristics either focused primarily on individual goals, individualistic cultures, or communal goals, collectivistic goals (Hall, 1976). Hofstede (2001) identified five dimensions of culture: (1) power distance, (2) uncertainty avoidance, (3) individualism and collectivism, (4) masculinity and femininity, and (5) long term and short term orientation. Power distance refers to the extent a culture values hierarchical power. India, where many international students immigrate from (Walker, 2000), for example, is a high-power distance culture because of the social implications the caste system still holds and values associated with positional power and wealth (Northouse 2016). Uncertainty avoidance is the degree a culture relies on set rules and values to maintain day-to-day activities. Individualism is concerned with a value for citizens to focus on their own unique goals, whereas collectivistic cultures make decisions that are best for the greater good. Femininity and masculinity is concerned with the value of gender equity in a culture (Hofstede, 2001). Long- term orientation refers to a culture’s value of future gains, whereas short-term orientation cultures are concerned with the present and the past (Hofstede, 2001). Cultures that are oriented towards to past value traditions; for example, many Middle Eastern and Asian cultures are past oriented (Northouse, 2001). Scholars suggest cultural dimensions influence how people experience leadership and lead.

The Globe Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness research program (GLOBE) examined culture and leadership. Using data from 17,000 supervisors representing more than 950 organization and 62 cultures, researchers developed nine cultural dimensions (House & GLOBE, 2004). The GLOBE cultural dimensions include: (1) uncertainty avoidance, (2) power distance, (3) institutional collectivism, (4) in-group collectivism, (5) gender egalitarianism, (6) assertiveness, (7) future orientation, (8) performance orientation, and (9) humane orientation.

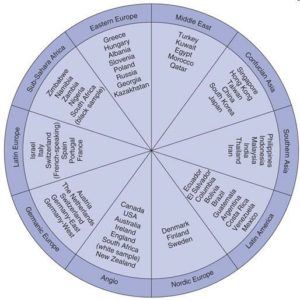

House and GLOBE (2004) developed cultural clusters to manage the analysis of their data. The clusters were created from prior research, and with consideration for shared language, proximity, and cultural norms. The 10 clusters include: Anglo, Germanic Europe, Latin Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Middle East, Confucian Asia, Southern Asia, Latin America, and Nordic Europe (House & GLOBE, 2004). Figure 1 shows the various countries that are represented in each cluster. According to House and GLOBE (2004) each cluster has unique cultural dimension rankings that influence how they experience leadership.

Figure 1: Country Clusters Per GLOBE (House and GLOBE, 2014)

Figure 1: Country Clusters Per GLOBE (House and GLOBE, 2014)

Furthermore, Astin’s (1993) Input-Environment-Outcome (I-E-O) conceptual model for student involvement offers yet another framework for this study. Inputs indicate that students’ identities, family background, and academic experiences influence their development. Environment is affected by various factors. Teaching styles, campus culture and climate, curricula, peers and faculty, student services, and other experiences while in college can all play a role. Outcomes are encompassing of the new knowledge, attitude, and skills students develop throughout their college experience (Astin, 1993).

Astin (1993) also identified five assumptions of student involvement. First, students should be invested, physically and psychologically, in the experience. Second, involvement is continuous and individual students’ experiences vary. Third, involvement can be measured qualitatively and quantitatively. Fourth, quality and quantity of involvement influences students’ outcome and growth. Finally, there is a correlation between involvement and academic success.

To summarize, Northouse (2016) defines leadership as a “process whereby one individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal” (p. 6). He defines culture as “learned beliefs, values, rules, norms, symbols, and traditions that are common to a group of people” (Northouse, 2016, p.428). Culture influences how people conceptualize leadership and their leadership practices. Therefore, international students’ cultures should theoretically influence their leadership involvement experiences in the U.S. Moreover, according to Astin (1993), international students’ involvement on campus should influence their development.

Method and Data Analysis

A phenomenological methodology was used to describe lived leadership experiences of international graduate students. Creswell (2013) defines phenomenological study as a method of describing “the common meaning of several individuals of their lived experiences of a concept or a phenomenon” (p. 76). The philosophical assumption of phenomenology is the essence of meaning is discovered through careful examination of the whole picture; it is about getting beyond what “appears” and unveiling what “really” is (Ihde, 1986, p.33).

Phenomenology is concerned with understanding the true essence of a human experience (Moustakas, 1994; van Manen, 1990). The researcher is not trying to explain what is going on, but is describing the phenomenon, and fully understanding the lived experience (Ihde, 1986). The researcher must suspend all judgements and perceptions, a process referred to as epoché, and focus on the phenomena (Ihde, 1986). Researchers must get their experiences out of the way of the true meaning of the phenomena and bracket themselves out when possible (Creswell, 2013). A bracketing interview was conducted by an experienced colleague of the researcher for this study. While seeking to understand the essence of a phenomenon, the researcher must beware of apodictic perceptions; undivided attention must be given fully to the phenomena and assumptions about what realities are most important should not be made until there is enough information to do so (Ihde, 1986). The researcher then must make an interpretation of participants’ lived experiences (van Manen, 1990). To ensure trustworthiness, member checking was used to provide participants an opportunity to critique the initial interpretations of the transcriptions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Long semi-structured in-depth interviews between 28 and 60 minutes were conducted using a variational method, probing, to attain the truest essence of the phenomena (Ihde, 1986; Polkinghorne, 1989). The data analysis process involved reviewing interview transcriptions to highlight significant quotes, a process known as horizonalization (Moustakas, 1994). Following the horizonalization step, the researcher dove into the transcriptions again, this time using the highlights to create clusters of meaning (Creswell, 2013). The clusters and highlights are used to describe the participants’ experience.

Reflexivity Statement. In qualitative research, researchers should acknowledge how their values and biases influenced the research process (Creswell, 2013). While I was not an international student, I was not born in the United States. My experiences growing-up in a different country and working on educational programs in various countries inspired me to conduct the study. As a student who has been involved on campus, I valued my experience and was curious about the experiences of international students who were involved on campus. I believe involvement can have positive outcomes for students. However, from my experience, very few international students take on leadership roles compared to native students. I conducted a bracketing interview to set aside my assumptions as to why international students were involved and what their experiences could be like. I assumed students had some challenges when they first arrived in the United States, but I was not sure about what moved them to get involved on campus. I also assumed that international graduate student leaders had some involvement experience in their home countries and that their undergraduate institutions likely did not encourage involvement.

Since I was interviewing students from different countries, I was intentional about capturing the voices of each participant. I understood that two participants form the same country could have a different experiences. I also had little knowledge about the higher education system in most of the countries where participants studied. Thus, I entered each interview open to hearing a different story. The findings supported my assumptions that international graduate student leaders had some type of involvement experience in their home countries. While the majority of their involvement was in their undergraduate institutions, some of it was not. In addition, my assumptions that undergraduate involvement was not encouraged was also supported by the findings.

Population and Sample. The population of this study consisted of international students who were, at the time of data collection, enrolled in a graduate program at a large land grant research institution in the southern United States. In addition, they must have been in a formal leadership role or were serving in one at the time of data collection. Participants included students who served in leadership roles in professional organizations, student government, cultural organizations, and other groups. Purposive sampling was utilized to recruit participants. A total of 17 participants took part in the study. Participants were between the ages of 22 and 34, and majored in a wide range of fields including biology, English, architecture, chemical engineering, international relations, and business. Seven participants were enrolled in master programs and 10 were in doctoral programs. Of the 17 participants, seven participants were female. The 17 participants represented students who did their undergraduate studies in 11 countries: Trinidad and Tobago, India, Nigeria, South Africa, Haiti, Honduras, Brazil, Iran, China, Indonesia, and Mexico. Two participants did an exchange program to the U.S. before starting their graduate studies, two worked on short-term projects in the U.S., one was an international student in undergrad, and another holds a dual citizenship with Italy.

Table 1 Characteristics of Study Participants

| Sex | Country of Study | Major | Degree | |

| P1 | M | Trinidad & Tobago | Agricultural Education and Communication | PhD |

| P2 | M | India | Chemical Engineering | PhD |

| P3 | F | Nigeria | International Public Relations | PhD |

| P4 | F | India | Biomedical Engineering | MS |

| P5 | F | South Africa | English Literature | PhD |

| P6 | F | Haiti | Master of Sustainable Development Practice | MDP |

| P7 | M | Honduras (from Ecuador) | Master of Sustainable Development Practice | MDP |

| P8 | M | India | Construction Management | MS |

| P9 | F | Brazil | Entomology & Nematology | PhD |

| P10 | M | Brazil

(Dual Italian citizen) |

Architecture | PhD |

| P11 | M | Iran | Construction Management | PhD |

| P12 | M | China | Management | MS |

| P13 | F | India | Computer Science | MS |

| P14 | F | China | Electronic Engineering | MS |

| P15 | M | Indonesia | Forest Resource and Conservation | MS |

| P16 | M | Brazil | Construction Management | PhD |

| P17 | M | Mexico | Biology | PhD |

Data Collection. In the present study, participants had the option to suggest the location for the interview. Most participants were interviewed in various locations on university campus. The principal researcher conducted all the interviews. Undergraduate research assistants were trained to help with transcriptions. Each interview was transcribed by one member of the research team and checked for consistency by a second member followed by participant member-check.

Results

Four themes emerged from the data: (1) contextually challenging, (2) essential, (3) task and people oriented, and (4) rewarding.

Contextually Challenging. The first theme that emerged from the data, shared by all participants, is the idea that leadership is contextually challenging. Although not all the participants served in formal leadership roles in their undergraduate studies, they all talked about how contextual differences make leadership more difficult in the United States. First, some participants thought they would be discriminated against, until they actually got involved and experienced otherwise. When asked about their leadership experience as an international student, one participant said “it was hard, I had thoughts I wouldn’t be welcomed, by different organizations… but I was wrong” (P8, India). Second, participants felt their spoken English proficiency and anxiety about communicating with native English speakers would be a barrier to leadership. One participant said, “Language is the first constraint” (P15, Indonesia). This sentiment was shared with almost all the participants. Language, as well as some cultural differences, makes it difficult for some participants to communicate and connect with other student leaders on campus. Another participant said, “I don’t think I was prepared to be a leader and I don’t know what would prepare me… without understanding the context… [Although] I speak English… my English is different from yours, I would say something that might offend you when I really don’t mean any offense” (P2, Trinidad and Tobago).

Lastly, participants showed continuous concerns of cultural differences. Not only are participants concerned about not offending others, they sometimes struggle with grasping social norms. One participant said, “Here, it’s more difficult for me. It’s mostly a language barrier, but also there is a cultural barrier… I don’t know what to talk about. I don’t know whether or not to bring a topic. I don’t know if they’re interested or even if they know what I’m talking about” (P11, Iran). Another participant said communication “was a challenge…what are the rules of communication or even meeting people… do you hug that person? Do you give him a kiss on his cheek…do you just do shake hands… took a lot of time [to] feel comfortable” (P2, India). What is also clear from the experience of students is engaging in leadership forces them to quickly work through these initial transitional issues. Consistent with other findings by Yoh and Pedersen (2006), Abe et al. (1998), and Toyokawa and Toyokawa (2002), the participants all described the benefits they have experienced because of their involvement.

Essential. The second theme that emerged from the data was how essential participants felt their leadership involvement has been. For international student leaders, getting involved was about self-care. Participants talked about having an innate need to be involved, a love for leadership, and getting involved to mitigate depression. One participant said, “You just need to study was my initial thought… I was trying to do [and] I become stressed – a lot of stress – so I need contact with people” (P7, Honduras). Another participant said “It was really, really hard for me… I was afraid to get…depressed… and second year [decided to] find a solution for my life here” (P9, Brazil). A participant from India, when talking about involvement in undergrad and their transition to the U.S. said “It was one the things that was in me… It’s something that motivates me, it keeps me alive… I was depressed for a week or two [in the U.S.] because I was not knowing any student here…it was hard times…I need to have interactions with other people” (P8, India). Many participants shared similar sentiments. There was a need for them to be involved out of interest, and for some it was get involved or go home. One participant said, “If I don’t have an extracurricular activity, I won’t be able to study. I need to keep that balance” (P13, India). It was evident that many participants have an essential urge to be involved.

From a leadership perspective, some participant also got involved because they felt a responsibility to the organization, wanted some form of control over organizational policies that could affect them personally, or wanted opportunities for personal development. One participant said the desire to “learn about leadership” and overcome “huge problem with problem speaking” inspired them to get involved (P16, Brazil). Another said, “I’m shy, and shy and I’m always trying to challenge myself…[and] I really want to participate in what’s shaping me, the rules that they’re imposing on me” (P6, Haiti). Many of the organizations that the participants are involved are very influential on the campus, some drawing thousands of students to their events and others advocate for issues that specific to international graduate students. For example, one organization receives funds to coordinate airport pick-ups when students are first coming into the U.S., they facilitate short home stays for these students, and provide them with a handbook. They provide an essential need to these students the university administration do not directly offer. Their ability to continue with providing these services is dependent on maintaining these funds. For some participants, there are a lot at risk with they do not play a role in keeping these organizations running. They get involved out of sense of responsibility. One participant, when asked about what inspired him to get involved said, “It was responsibility you know. I think it’s probably something like loyalty to an organization” (P12, China). International graduate students described their leadership involvement experience as essential.

Task and People Oriented. Connected to this idea of involvement being essential for international graduate students, participants largely described leadership as a collaborative management process – that is an act of service. One participant said, “for me, leaderships is about managing…people…time…some kind of activity to achieve your goals… leadership is also persistence and also patience” (P15, Indonesia). Other participants said the leader “[ensures] everything is fine… [and that] the final product is presentable, “involves everyone in the decision making,” and “[has] the ability… to work in a team, to manage and participate in a team with a group of people” (P4, India; P16, Brazil; P11, Iran). For international student leaders, there is an element of task orientation when it comes to leadership. The leader has these responsibilities to delegate, have clear objectives, and accomplish goals. However, the leader must be participatory. Leadership is about a responsibility, often to their cultural groups, and not about power. As they manage the day-to-day operation, they recognize they are serving a population. As some participants said leadership is about “understanding your team, working with that team… not [about] what you want,” and “walking with, giving space to, and being the voice that invites…inviting people to be [their] greater selves” (P2, India; P5, South Africa).

There is this greater implication for leadership that goes beyond title and management. One participant said “the true nature of leadership is for you to serve those people” (P3, Nigeria). The participants have a strong desire to serve their community, but they were also concerned with the work that needs to be done. They recognized the value of the work they were doing, especially for members, and wanted ensure their organizations continued to meet the needs of the community.

Rewarding. The final theme that emerged from the data is how rewarding involvement has been for the participants. The rewards for involvement take several forms. For some participants, they have been able to build their social capital. Others have learned critical leadership skills or used the experience as an opportunity for personal growth. First, all participants said their experience, although challenging, has been positive. One participant talked about the process learning to find the space at the university. Reflecting on how her identity as an international graduate student leader who is female, black, and from South Africa, she said “I come from a worldview, a perspective, where community is the focus, and here the individual is the focus. So, you have a privilege position to recognize the ways in which individualism harms the community, but you also can learn so much about what it means to actually put yourself at the center. So, there’s healing there that can happen. Here you are and you as an individual never really mattered, because the community is the focus, and here’s a space that says you do. You rise to the occasion to heal those parts of you that yearned to be at the center” (P5, South Africa). This narrative captures the essence of how international graduate students, considering the cultural dimensions, can benefit from being in a culture that is different (House & GLOBE, 2004).

In many ways, although most participants valued their undergraduate experience, their leadership experience as an international graduate student has added to their development. One participant said, “[Brazil] prepared me a lot, but here I get like the upgrade” (P9, Brazil). Several participants talked about how they have been able to network and the personal and professional benefits of those relationships. Participants also shared anecdotes about how involvement has helped them learn “decision making skills,” “time management,” “leadership,” and has helped build “resilience” and “grit” (P2, India; P8 India; P9, Brazil; P11, Iran, P17, Mexico). Other participants also talked about how leading at the university in the U.S. was easier because of the resources (personnel and funds), freedom to be innovative, and having a voice (P3, Nigeria; P12, China; P14, China). Overall, participants described worthwhile benefits for being involved in leadership experiences.

Discussion and Summary of Findings

The purpose of this study was to describe the lived leadership experience of international graduate students in the United States. Using the GLOBE framework on leadership and culture, and Astin’s (1993) I-E-O model as conceptual frameworks, there are several conclusions to be made from this study. In this section, summary of findings, recommendations, and limitations are discussed.

International Graduate Student Leadership. The 17 international graduate students who participated in this study were all, at the time the interviews were conducted, serving in a formal leadership role. Their leadership experience as students were challenging because of contextual differences; however, involvement was essential to their growth and well-being. They perceive leadership as management that was collaborative, but service-oriented. Lastly, their involvement in leadership was rewarding.

Leadership is contextual. Cultural differences influence the leadership experience of international students. Throughout the narratives aspects of cultural dimensions came up. Whether it was power distance, individualism and collectivism, or uncertainty avoidance – the dimensions informed how participants experienced leadership in their home country and how they were attempting to reconcile the differences as leaders in the U.S. (Hofstede, 2001). None of the countries where the participants complete their undergraduate studies are in the same country cluster as the United States, “Anglo” (House & GLOBE, 2014). Although one participant is from South Africa, only white sample is included in the “Anglo” cluster. The black sample is in the “Sub-Sahara Africa” cluster. While there are similarities between the clusters, there are some significant differences. There were participants from four of the 10 clusters, though not all countries are listed in a cluster (See figure 1). International students experience some of those differences as they transitioned into the U.S. While their understanding of leadership does not change drastically, they recognized they had to adapt their leadership style in their roles compared with what was culturally accepted in their home countries.

Consistent with other findings, international students, upon arrival, often struggled with communicating with locals (Harik-Williams, 2003; Zhang & Zhou, 2010). Many fear being ridiculed for their accents, being misunderstood, and not knowing how to connect. Participants talked about not being sure of what topics to discuss, how to greet locals, and meanings of local vernacular. Even with some of the challenges, international students experienced leading in a different cultural cluster, they described their leadership involvement as essential (Gardner & Barnes, 2007). Many had this innate desire and need for leadership and community. Particularly for participants who were involved in activities in the home countries, they still had a desire to be involved while they study in the U.S. For some international students, not finding a community can lead to homesickness, depression, or academic failure. Involvement can be a form of self- care for international students.

International students also feel a sense of responsibility for why they should get involved. Almost all participants held leadership positions in cultural organizations. The responsibility of supporting peers coming from their home countries and being a representative for their country was revered. In many ways, the leadership work these students do contribute to the success of an untold number of other international students. Some of the leaders have created handbooks that they distribute to incoming students. Being from the same country and having similar experiences position them, more than university personnel, to better provide relevant resources to international students.

International students conceptualize leadership as a collaborative management process that is service-oriented. Leadership is about organizing people, identifying common goals, and working together to accomplish these goals (Northouse, 2016). The overlying perception of leadership was that it is primarily task-oriented, followed by a high concern of people and teamwork. International student leaders recognized they are working in service of their constituents. They are concerned with doing good work that will benefit the members of their respective organizations. Even with a focus on management, the need for collaboration, participation, and inclusion was not lost. They shared a value for team leadership.

Lastly, international graduate students have had a rewarding leadership experience. Many have expanded their network and built meaningful relationships through their involvement. These findings are supported by Gardner and Barnes’ (2007) work on graduate student involvement. They also have had opportunities, as student leaders, to do work they would not have been able to do in their home countries because of the support the university provide for student groups. Funds, access to meeting rooms other services make leading and involvement a bit easier. International students have also learned valuable skills around leadership, communication, diversity, and have gained opportunities for personal and professional development because of their involvement. The benefits international students experience because of their leadership involvement are supported by several key findings from studies on student involvement (Astin, 1993; Moore, Lovell, McGann, & Wyrick, 1998; Tinto, 1993)

Implications and Recommendations. The findings of this study have implications for mental health counselors, student services, faculty, international student centers, and other professionals who work with international students. Campus mental health counselors should be trained to talk to international student clients about their experiences in their home countries. When students experience role and culture shock, it can often send them into depression. Helping students identify ways they can still be themselves in a new culture can be beneficial. Many of the participants who were involved in their home countries struggled to adjust until they could find ways to get connected on campus and leadership experiences can provide one potential outlet.

International student centers can offer optional conversation partner matchings to help students become more confident in their spoken English fluency. Facilitating programs that forces international and domestic students to intermingle can be extremely beneficial. In addition, there should be leadership development and involvement workshops for international students. Many international students are coming from countries where leadership and student involvement are viewed differently. Almost all of the participants talked about how student involvement was not encouraged in their home countries. Participants who were involved, discussed how different student involvement is in the U.S. compared to their home country. International student centers can create programs that help students understand the involvement culture in the U.S. and its benefits. It would also be beneficial to allocate time during international student orientation to discuss student involvement.

Based on the findings, international student leaders provide a great deal of support for their peers. Student services and other professionals who support international students should partner with student organizations that serve a high number of international students to maximize their reach. For example, participants talked about some of the work they do to help incoming students from their home countries. They provide rides from the airport, short-term housing, a pamphlet with important information, and many more. Professionals working with off-campus housing can work with some of these organizations. Given some the work international students, through campus leadership involvement, are doing to support their peers, it is essential funds are allocated to support their efforts. They provide student services that most institutions do not have the capacity to offer.

In addition, student life professionals should coordinate workshops for international students who are in leadership roles across campus. This will help facilitate their growth and development, and provide opportunities for them to learn from one another. While some participants had figured out ways to help their peers, others were still struggling. Facilitating time where these students come together to learn how to make money requests or reserve a room, they can also provide valuable support to one another. Faculty advisors and mentors can also help international students transition by encouraging involvement in student activities within the first semester. Faculty members can also serve as advisors to student organizations that cater to international students.

Furthermore, leadership educators should create programs that build on students’ experiences with leadership. While the participants were leading in the U.S. context, many of them were leading peers from their home countries. Leadership programs that target international students should help students add to their leadership knowledge, instead of only learning a western concept of leadership.

Finally, the findings have critical theoretical implications. First, involvement in formal leadership roles on campus can contribute to international graduate students’ satisfaction. While studies on student involvement has primarily focused on American undergraduate students, the findings described the level of impact involvement can have on international graduate students. Second, this study explored the experience of international students leading in the United States. House and GLOBE (2004) work on culture and leadership did not account for what happens when members from one country cluster becomes a leader in a different cluster. This study begins to explore this concept. Finally, the graduate student voice is missing from student involvement theory. Student involvement theory should be encompassing of all students, including graduate and international students.

Limitations and Future Research. While this study offers great insight into the experiences of international graduate student leaders, few limitations should be mentioned. First, most the participants were leaders of cultural organizations, in which they identify. Future studies should explore the experience of international students with other types of involvement. Specifically, future studies could focus on involvement where they interact with others who are not from their country of origin. Second, the participants were all students at the same university. Future studies should compare the experience of international student leaders from other institutions. Third, all the participants were graduate students. A study on international undergraduate students can further explore the impact of involvement for international students. Lastly, the participants represented only 11 countries and there were country clusters not included. Future research should compare the leadership experiences of international students from different parts of the world. Furthermore, future research should explore the experiences of international students who are not involved in leadership.

Conclusion

The data showed international graduate students benefit a great deal from their leadership involvement experience. International graduate students also described their leadership involvement in the U.S. as being contextually challenging, but an essential component of their graduate studies. For international graduate students, leadership is about management and teamwork, but also service-oriented. Overall, their experience as leaders in the U.S. has been rewarding. Professionals who support international graduate students should invest in leadership development programs, facilitate more interactions with national students, and continue to fund cultural organizations on college campuses.

References

Abe, J., Talbot, D. M., & Geelhoed, R. J. (1998). Effects of a peer program on international student adjustment. Journal of College Student Development, 39(6), 539.

Arthur, N. (2004). Counseling international students: Clients from around the world. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college?: Four critical years revisited (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bourke, A. (2000). A model of the determinants of international trade in higher education. The Service Industries Journal, 20(1), 110-138. Doi:10.1080/02642060000000007

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Farley, K., McKee, M., & Brooks, M. (2011). The effects of student involvement on graduate student satisfaction: A pilot study. Alabama Counseling Association Journal, 37(1), 33-38.

Gardner, S. K., & Barnes, B. J. (2007). Graduate student involvement: Socialization for the professional role. Journal of College Student Development, 48(4), 369-387. Doi:10.1353/csd.2007.0036

Gareis, E. (2012). Intercultural friendship: Effects of home and host region. Journal of International and Intercultural Communications, 5(4), 309–328.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York: Doubleday.

Harik-Williams, N. (2003). Willingness of international students to seek counseling (Doctoral dissertation, Ph. D. dissertation, The University of Akron, United States—Ohio. (UMI No. AAT 3083396).

House, R. J., & Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Program. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Huntley, H. (1993). Adult international students: Problems of adjustment. Athens, OH: Ohio University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 355 886).

Ihde, D. (1986). Experimental phenomenology: An introduction. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Institute of International Education. (2014). Open doors report on international education exchange. New York, NY: Institute of International Education.

Lee, J. J., & Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. Higher Education, 53(3), 381-409. Doi:10.1007/s10734-005-4508-3

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Mamiseishvili, K. (2012). International student persistence in U.S. postsecondary institutions. Higher Education, 64(1), 1-17. Doi:10.1007/s10734-011-9477-0

Moore, J., Lovell, C. D., McGann, T., & Wyrick, J. (1998). Why involvement matters: A review of research on student involvement in the collegiate setting. College Student Affairs Journal, 17(2), 4.

Moores, L., & Popadiuk, N. (2011). Positive aspects of international student transitions: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of College Student Development, 52(3), 291-306. Doi:10.1353/csd.2011.0040

Mori, S. C. (2000). Addressing the mental health concerns of international students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78(2), 137-144. Doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02571.x

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2014). Education at a glance 2014: OECD indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Schweitzer B., Morson, G., & Mather, P. (2011). Understanding the international student experience. Baltimore, MD: American College Personnel Association

Smith, C. (2016). International student success. Strategic Enrollment Management Quarterly, 4(2), 61-73. Doi:10.1002/sem3.20084

Smith, C., & Demjanenko, T. (2011). Solving the international student retention puzzle. Windsor, Ontario, Canada: University of Windsor.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

Toyokawa, N., & Toyokawa, T. (2002). Extracurricular activities and the adjustment of Asian international students: A study of Japanese students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26(4), 363-379. Doi:10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00010-X

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Walker, D. A. (2000). The international student population: Past and present demographic trends. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 27(2), 77.

Yoh, T., & Pedersen, P. M. (2006). Assessing satisfaction with graduate sport management programs: An examination of international students’ academic contentment. The ICHPER- SD Journal of Research in Health, Physical Education, Recreation, Sport & Dance, 1(2), 12.

Zhang, A., & Zhou, G. (2010). Understanding Chinese international students at a Canadian university: Perspectives, expectations, and experiences. Comparative and International Education, 39(3), 1–16.

Author Biographies

Sky Georges is a PhD candidate in agricultural education and communication with a concentration in leadership development in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Florida. He can be reached at sgeorges@ufl.edu

Dr. Huan Chen is an assistant professor of advertising in the School of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida. She received her Ph.D. in communication and information from the University of Tennessee. Her broad research interest is new media and communication. She can be reached at huanchen@jou.ufl.edu.