Introduction

Leadership education in recent years has increasingly drawn interest by those in both the academic and professional world. The program described herein was designed for individuals of all organizational levels, not simply management. Students diagnose leadership from both an individual and an organizational level through analyzing, examining, and identifying various components and behaviors of the leadership process as it relates to every level within their organizations. We further stress the importance of building relationships and not to be a boss but be a leader. Historically, schools of management took the front stage in developing those individuals who would become the eventual heads of major organizations and companies. The approach to leadership education was based on industrial age concepts, according to Rost and Barker (2000), because it was management oriented and had a “presumed top-down, hierarchical structure; it is goal oriented; where the goal is defined by some level of organizational performance; it focused on bureaucratic efficiencies; it is centered on self-interest; it was founded on materialism; it is male (or male characteristic) dominated; it uses utilitarian ethics; and, it uses quantitative methods to solve rational/technocratic problems” (p. 4).

As Kotter (1996) reminds us, there is a difference between management and leadership but both are needed within organizations. While management is often associated with tasks, leadership is often associated with systemic thinking, relationship building, and influence. It may also be argued that while management is focused around a particular position, leadership is often focused on a process. Rost and Barker (2000) contend that “postindustrial leadership should be based on the assumption that leadership is the result of the intentions and actions of numerous individuals—the sum of individual wills—rather than the result of one individual’s will and action… must address the nature of the complex social relationships among people who practice leadership, and it must characterize their purposes, motives, and intentions” (p. 5). Given this information, what should be the focus of the coursework in an organizational leadership program? Should it be less about the theory and more about application or should it be a combination of both? Should it solely address the skills required of a leader or emphasize the socially constructed nature of leadership? In addition, what kinds of learning activities or instructional strategies should be used to provide students a holistic understanding of the leadership process?

Questions such as these are reasons behind the creation of the Inaugural National Leadership Education Research Agenda (INLERA). Although leadership was being researched, the educational application of such research was lacking in practice (Andenoro et al., 2013). Andenoro (2013) further asserts that, “this has been a difficult proposition for the field of Leadership Education historically” and claims it is the distinctiveness of the knowledge within a certain discipline that defines it as a credited field of study (p. 2). The National Leadership Education Research Agenda was formulated in order to begin to solidify and standardize the focus of leadership education programs.

Our work seeks to provide support for the National Leadership Education Research Agenda by “increasing the applied nature of the scholarship guiding the development of future leaders and managers” (Andenoro, 2013, p.3) and the application of some of the National Agenda items including:

- A transdisciplinary perspective in the curriculum development which included team- based approach to course development with an instructional designer (Priority One).

- Explore the capacity and competency development process for the leadership education learner through established embedded assessments (Priority One) and establish collaborative capacity for programmatic assessment (Priority Two) throughout the program that inform a final applied final capstone course which requires an applied research project.

- Explore the role of the individual learner (Priority One), Development of Leader, Follower, and Learner psychological capacity (Priority Three) through discussions (online and face-to-face) and reflective essays that require the learner to relate leadership, ethical, and organizational theories to their own practice or situation and allow time for reflection on those practices.

- An exploration of curriculum development frameworks to enhance the Leadership Education transfer of learning through the conceptualization of core coursework (Priority One).

Along with the structure provided by the National Research Agenda, other factors affect leadership education, such as the change from an industrial to a knowledge-based society (Weert, 2006, p. 218) and need for lifelong learning (Yapp, 2004, p. 64). Lifelong learning is an important consideration because workers, on average, stay in positions for 4.4 years (Forbes, 2012, para. 1). Leaders can expect Millennials to change jobs approximately 15 to 20 times throughout their life (Forbes, 2012, para. 2). These issues further complicate leadership education initiatives as we strive to provide the transferable skills future leaders will need. The new leader will need to understand and manage interdependent workplace relationships that allow for “win-win partnerships” (Yapp, 2000, p. 62). The knowledge society calls for a “new educational professionalism” (Weert, 2006, p. 235) requiring that leaders participate “in a continuous process of innovative change, necessitating lifelong learning” (p. 235). Further, Sowcik and Allen (2013) contend that leadership is interdisciplinary in that many different disciplines “inform and can be informed by the topic of leadership” (p. 62). Given these changes and the interdisciplinary nature of leadership education, how can we develop a program that will help students make sense of their working environment and develop their professional leadership practice? Not all the aforementioned questions can be fully addressed, however, we attempt to provide insight to them by explaining our design, learning activities, and pedagogical framework. Since this program has just recently begun, there is not yet empirical data to examine.

Proposed Framework and Pedagogical Basis of Master’s Program

The Master of Professional Studies degree in Organizational Leadership is offered to professionals from various entities such as government, non-profit, education, business, and the community, and provides students with the knowledge and skills to become effective leaders of change in the complex and dynamic workplace environment. Students will further develop foundations in ethical leadership, communication, research, and management, while specializing in either organizational development or information systems management. The program employs a collaborative, applied concepts approach to learning in a blended format. Rabin (2013) from the Center for Creative Leadership states:

Blended Learning for leadership must go beyond coursework to engage leaders in the domains of developmental relationships and challenging assignments, which research shows is critical for leader development. Redefining the blend to bring learning closer to the workplace – and provide appropriate “scaffolding” for the learner’s needs – is still a struggle for most organizations. (p. 1)

It was this insight that influenced and informed the decision to offer the courses in a blended format and to create an applied degree.

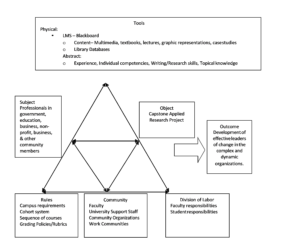

The framework of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) was used as the lens to examine the interaction and interplay of teaching and learning as we created the curriculum for the program. Why choose activity theory? CHAT is used to help analyze object-oriented activity which “refers to mediational processes in which individuals and groups of individuals participate driven by their goals and motives, which may lead them to create or gain new

Figure 1: CHAT Model as applied to the leadership degree program

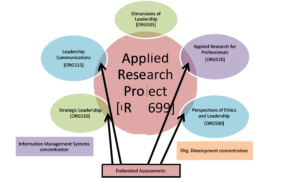

The development of the Organizational Leadership curriculum focused on two main areas, continuity of courses, and the inclusion of embedded assessments, which informed the final capstone research project. Both horizontal and vertical continuity were considered in the development of the curriculum to establish some consistency with the overall views of the field of leadership studies and to ensure that key concepts were repeated throughout the program at varying depths and applied to different areas, also known as a spiral curriculum (Bruner, 1960, p. 13). The second focus was on the connectivity of the embedded assessments within each of the core courses that then become the course objectives in the final applied research capstone project (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Core Curriculum conceptualization

As Figure 2 indicates, our main concern focused on the culmination of knowledge and skills that will be applied and assessed within the leadership Applied Research Capstone Project. Surrounding the Applied Research Capstone Project are courses reflecting what Andenoro (2013) pointed out as the “tangible connections to decision-making, ethics, morality and organizational culture” (p. 2). We took the previously mentioned concepts and skills and expanded them to include applied research, communications, and, of course, leadership theory. As the curriculum was developed, students’ or subjects’ (Figure 1) background—their prior knowledge and work experience—was considered. Next, we conducted an analysis of the interaction (indicated by the arrows in the CHAT model) between the students, the community(ies) in which the student resides, the division of labor, rules and the tools that were available to the students.

First, we considered how their work communities and college communities could support and/or hinder their efforts. For instance, we asked the question, would all students be able to or want to use their work setting as a basis for their applied research paper? We concluded that they would not and offered an alternative option through our Educational Foundation for students to work with a non-profit organization in our area.

Second, we looked at the division of labor and the rules that would affect students as they progressed through the program. Faculty and student responsibilities were discussed. Faculty would act as guides throughout the course, allowing students to take charge of their own learning with guidance. Guidance would take the form of mini-tutorials that would cover concepts that were not understood, such as tutorials on statistical computation, just-in-time discussion comments that would correct, inform, or lead the conversation regarding key concepts, and multimedia lectures developed using Camtasia that communicate the stories, illustrations, and antidotes that aid in student understanding.

Last, an analysis of the student interaction with the tools was undertaken. This analysis included review of the physical tools they would use, the learning management system, library resources, and the course content, as well as the abstract tools, their experience and writing skills. As a result of the analysis, a technical overview of the learning management system was developed and would be delivered in the introductory session before the courses began. In addition, a Getting Started document was created that would be available to students in every course that provided information concerning technical components of the course, information literacy, and various college contacts. Courses were developed using a master course design. A master course design assures that the same instructional objectives and embedded assessments are consistently used within each course. The principles outlined in the Quality Matters™ rubric were followed as we created each course.

Finally, the core course content was analyzed. It was important for our team that the role of research was intertwined and emphasized throughout all courses and that students used current research when applying leadership ideas within their organizations. The five courses (15 credits) below collectively make up the core of the degree and the conceptual model in Figure 2. These courses include the following:

-

[ORG500] Perspectives of Ethics and Leadership: This course is designed to prepare students to meet the ethical leadership challenges and opportunities they will encounter within organizations, as well as emerging leaders in various professional fields. Ethics is a foundational component of leadership. The course provides cases in which students will analyze and apply ethical philosophies and theories to the decisions and behaviors of leaders. Students will also assess and reflect on their own ethical, leadership, and followership styles. The course further examines codes of ethics for the students’ respective fields.

-

[ORG505] Dimensions of Leadership: The objective of this course is to study the major theories of leadership in order for students to improve their ability to use the basic skills of leadership, as well as examine the various approaches to leadership. This course allows students to identify and evaluate contemporary leadership issues in today’s complex society.

-

[ORG510] Strategic Leadership: The purpose of this course is to introduce graduate students to strategic planning management; a big picture course cutting across all organizational functions by centering on the whole enterprise. Strong strategic planning and sound execution by management leads to positive organizational performance.

-

[ORG520] Applied Research for Professionals: This course is the study and application of the different methodologies of research appropriate for professional studies. Students will utilize case studies to explore the purposes and applications of applied research. Students will explore paradigms and methods for designing and conducting effective research in addition to interpreting and analyzing the data to implement realistic and sustainable solutions.

- [ORG515] Leadership Communications: This course introduces key elements of professional and technical communications. Course topics include information literacy; user-centered writing and design; communicating with diverse audiences; ethical communications; informational design; and technical writing styles. Through these topics, the course will approach practice of leadership from a communication perspective.

These five core courses set the foundation for the student’s capstone experience that is described as:

- [ORG699] Applied Research Capstone Project: A capstone in professional studies including applied research is required to complete the program. Students must design, execute, and present a personal project, which synthesizes and applies selected knowledge, skills, and experiences appropriate to the students’ personal and professional goals and/or their chosen area of specialization.

Each of the five courses has several learning objectives and contains one embedded assessment. Embedded assessments are required to be completed regardless of the instructor who teaches that course and are a compilation of the different aspects critical to the process of leadership regardless of organization. The objectives of the embedded assessments collectively become the overall learning objectives of the Applied Research Capstone project which includes a case analysis (ethics), article reviews and reflective paper (leadership theory), a methodology proposal (applied research, organizational review/strategic plan exercise (strategic leadership), and a persuasive presentation (leadership communications).

In conjunction with the core coursework, four concentration courses (12 credits) in organizational development or information management systems inform the capstone project. These concentrations emphasize the concepts and skills leaders need to understand from a high level, organizational view. In both concentrations, the courses focus on four themes such as organizational change, sustainability, conflict resolution, and behaviors within organizations.

The capstone project was designed to be an applied micro level organizational change within the students’ place of employment or other organization, framed in leadership theory and informed by both the literature and real world analysis of their environment. Students are required to utilize a method appropriate in applied research to support their project. Students also need to be able to communicate and influence their proposed change and identify and address all ethical issues involved with their change. Through student interactions with coursework, other students, and instructors, the Organizational Leadership program was designed to maintain a balance between the traditional academic theory and real world relevance through attention to scientific methodological processes in applied research and also relevant real-world course exercises that are shown to be impactful to students of leadership within their professional world. The overall design of the curriculum focused on student-centered learning which is supported by teaching and learning paradigms (CHAT, spiral curriculum) and culminates with a capstone project. The capstone project is a systematic and holistic final piece of work that combines sound research skills, current practices in the students’ chosen concentration, and leadership theory as it applies to a real world issue.

Lastly, it is important to recognize when designing a degree curriculum there are many systems that need to be satisfied either currently or in the future as the program evolves. Two systems that impacted the development of the program were changes in the structure of Central Penn College and the influence of national accrediting boards.

The first system that impacted the development of the program was the creation of the School of Graduate and Professional Studies. Recently, our college restructured itself into four schools: School of Applied Sciences, School of Business and Communications, School of General Studies, and a new school, the School of Graduate and Professional Studies. This program was placed within the School of Graduate and Professional Studies as a standalone discipline whose core curriculum can be applied to other concentrations. By structuring the graduate program in this way, students can learn the basic concepts, theory, and skills needed to be a leader while also applying those skills within their own discipline or concentration.

Secondly, integrating and aligning our curriculum to standards or proposed standards of the National Research Agenda and those bodies that accredit leadership programs strengthen our program as we work toward accreditation. The most recognized accrediting agency of leadership programs currently is the Academy of Strategic and Entrepreneurial Leadership. Candidacy requirement set forth by Academy of Strategic and Entrepreneurial Leadership (ASEL) handbook states (preparing for leadership accreditation):

A Member must have students enrolled in each of the degree programs, which it will be submitting for accreditation consideration, and those programs must have been in existence for a sufficient period of time to make possible an evaluation of quality. The institution should be able to produce information concerning student achievement, and evidence of processes for curriculum development, and faculty development and evaluation. The Member must actually graduate students prior to achieving accreditation. (p. 5)

Additionally, standards from the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) were examined and integrated into the curriculum. Under the AACSB Assurance of Learning Standards, they list the following as managerial/leadership competencies:

-

-

- Communication abilities

- Ethical understanding and reasoning abilities

- Analytic skills

- Use of information technology

- Dynamics of the global economy

- Multicultural and diversity understanding

- Reflective thinking skills (Eligibility Procedures and Accreditation Standards for Business Accreditation, 2012, p. 72)

-

While we understand this agency does not currently accredit leadership programs, we thought it would be a benefit to our students and the overall strength of the program to adhere to their leadership philosophies for possible future considerations should they begin to accredit leadership programs.

Conclusion

The future of leadership education has only begun. As the focus shifts toward leadership as its own discipline, greater attention will be placed on the design of curricula and programs. More importantly, as the National Leadership Agenda gains recognition so too will the creation of such programs. Throughout the article, we have discussed the creation of courses that align with field-recognized competencies as well as a spiral pedagogical approach to educate student on the processes, principles, and theories of leadership. The thoughtful creation of assessments within the courses reinforces not only the competencies of leadership, but also the process of it. We understand CHAT may not be the only lens on which to build a leadership degree, for us it has been very useful. We also suggest examining accrediting bodies’ standards (ASEL, AACSB, and INLERA) to formulate the objectives, courses, and curriculum for optimal student outcomes and future consideration of your program for accreditation.

As we have mentioned earlier, data has not yet been captured to truly assess what has been outlined throughout this paper. However, once the first cohort completes all the core courses the program faculty, along with our instructional designer, will be reviewing the data collected from the embedded assessments within those courses. The faculty and instructional designer, using the CHAT model and instructional design principles, will evaluate the data using the results to inform any modifications that need to be made in the program’s courses or in the final applied research capstone project. In addition to the core courses, objectives, and assessments being reviewed, attention will also be placed on the continuity of the courses to more closely reflect the universally recognized concepts of the process of leadership.

References

Academy of Strategic and Entrepreneurial Leadership. (2012). Academy of Strategic and Entrepreneurial Leadership accreditation handbook. Arden: Author.

Andenoro, A. C., Allen, S. J., Haber-Curran, P., Jenkins, D. M., Sowcik, M., Dugan, J.P., & Osteen, L. (2013). National leadership education research agenda 2013-2018: Providing strategic direction for the field of leadership education. Retrieved from Association of Leadership Educators website: http://leadershipeducators.org/ResearchAgenda

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Eligibility Procedures and Accreditation Standards for Business Accreditation (Rep.). (2012, January 31). Retrieved April 22, 2014, from AACSB International – The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business website: http://www.aacsb.edu/~/media/AACSB/Docs/Accreditation/Standards/2012-business- accreditation-standards-update.ashx

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. New York: Harvard Business School Press. http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeannemeister/2012/08/14/job-hopping-is-the-new-normal- for- millennials-three-ways-to-prevent-a-human-resource-nightmare/

Rabin, R. (2013). Blended learning for leadership: The CCL approach. The Center for Creative Leadership. Retrieved from www.ccl.org/leadership/pdf/research/BlendedLearningLeadership.pdf

Rost, J. C., & Barker, R. A. (2000). Leadership education in colleges: Toward a 21st century paradigm. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 7(1), 3-12. doi:10.1177/107179190000700102

Sowcik, M. & Allen, C. (2013) Getting down to business: A look at leadership education in business schools. Journal of Leadership education, 12(3), 57-75. doi:10.12806/V12/I3/TF3

Weert, T. (2006). Education of the twenty-first century: New professionalism in lifelong learning, knowledge development and knowledge sharing. Education and Information Technologies, 11, 3-4.

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2010). Activity systems analysis methods: Understanding complex learning environments. New York: Springer.

Yapp, C. (June 01, 2000). The knowledge society: the challenge of transition. Business Information Review, 17, 2, 59-65.