Introduction

Collegiate leadership education programs have become standard on many college campuses since the mid-1990s with over 2,000 leadership programs, both curricular and co-curricular, listed in the International Leadership Association (ILA) Directory of Leadership Programs (Guthrie, Teig, & Hu, 2018). Co-curricular leadership programs are usually non-credit earning and typically offered by one or more departments within a university’s Student Affairs division; these co-curricular opportunities play an essential role in undergraduate student life, providing lasting college experiences that help guide students toward becoming productive citizens. A growing number of institutions also include credit-earning undergraduate curricular leadership programs in one or more disciplines that explore and educate students on leadership theory and practical application of leadership concepts (Komives, Lucas, & McMahon, 2013; Guthrie et al., 2018). Both are valuable to students’ personal and professional development.

Issue Statement

Despite the value recognized in curricular and co-curricular leadership programs and the expertise available by higher education professionals in both institutional divisions, programs continue to operate independently in many institutions (Manning, Kinzie, & Schuh, 2006; Owen, 2012). Universities that offer leadership education and development through formative partnerships across university divisions are uniquely positioned to leverage the expertise of professionals in both Academic and Student Affairs to enrich and expand their students’ experiential leadership education and development opportunities.

This application paper discusses boundary-crossing partnerships at one mid-western university. Early initiatives evolved from workshop collaborations into ongoing partnerships that have produced credit-earning special topics courses, a credit-earning student leadership practicum, and additional co-curricular, faculty-led workshops at Student Affairs leadership training and development events. From these collaborative efforts, nearly 300 students have participated in one or more academic credit-earning experiential leadership education and development opportunities, and many others have engaged in non-credit earning leadership experiences led by faculty from the academic leadership programs at the university. This paper discusses the evolution and outcomes of these partnerships and provides recommendations for exploring and implementing boundary-crossing partnerships.

Review of Related Literature

Leadership educators in higher education are those who facilitate leadership learning through both credit and non-credit-earning programs (Seemiller & Priest, 2015). Effective leadership programs guide students in developing their capacity to recognize that practicing leadership is not dependent upon position or title, but can be accomplished as a leader or as an active participant working with others toward a common purpose (CAS, 2019; Manning & Curtis, 2019; Owen, 2012). Regardless of the curriculum or where the leadership program resides, a central premise is the understanding that doing leadership is an inherently relational, social process in which individuals work together to achieve shared objectives (Van Vugt & Ahuja, 2011; Yukl, 2012). The Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS) Standards for Student Leadership Programs (SLPs) emphasize that SLPs must be intentionally designed and based on principles of active learning (CAS, 2018).

Active & Experiential Learning. Active learning models place emphasis on active student engagement and skill development rather than the instructor simply transmitting information to students (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). The effectiveness of active versus passive learning has been researched and validated extensively since the early 1980s. Chickering and Gamson (1987) identify active learning as one of seven best practices in undergraduate education, emphasizing that learning is not a “spectator sport” but a process that goes beyond passive classroom listening (p. 4). Instead, students engage in structured, student-centered activities such as reading, writing, discussing, and problem solving, all designed to challenge students to apply higher-order thinking skills for course content analysis and evaluation (Chickering & Gamson, 1987) and develop skills for the twenty-first-century workplace (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2008).

Chickering and Gamson (1987) emphasized that active learning is not limited to the classroom; structured learning experiences outside the classroom such as internships and practicums also provide students the opportunity to “make what they learn a part of themselves” (p. 4). Dewey (1897), perhaps the most well-known champion of experiential education, is often quoted from his pedagogic creed where he emphasized that progress in one’s education is a result of “new attitudes towards, and new interests in, experience” and “a continuing reconstruction of experience” (p. 79). He supported this premise with significant theoretical foundations in his work, Experience in Education (1938). As Dewey (1938) explains, experiential learning enhances the active learning process by moving beyond the classroom and into the realm of first-hand experience that is transformed into knowledge through intentional, reflective thought.

Drawing on Dewey’s (1938) work and that of other notable twentieth-century human learning and development scholars “who gave experience a central role in their theories,” Kolb (1984) produced an holistic model of experiential learning (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, p. 194) (refer to Figure 1). Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model provides a cyclical framework that supports the premise that students learn best from active learning that provides concrete experience and is followed by reflective activities from which they construct knowledge. The four stages of Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model are as follows: concrete experience (doing), reflective observation (observing), abstract conceptualization (thinking), active experimentation (planning).

Figure 1. Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model (ELM)

The National Society for Experiential Education (NSEE) offers eight principles to guide experiential learning activities (NSEE, 2013) (refer to Table 1). Central to these principles is “reflection,” described as “the element that transforms simple experience to a learning experience” in which the learner considers the experience, testing assumptions, decisions, and actions in context with past experiences and future considerations to internalize and build knowledge (NSEE, 2013, para. 5). When faculty integrate learning into the students’ experiences and help students build knowledge from what they know, students construct meaning based on the evidence of the experience. Baxter Magolda (1999) describes this process as self-authorship, or one’s ability to internalize and construct one’s ways of thinking and suggested that it is essential for navigating adult life.

Relational Leadership and Experiential Learning. The Relational Leadership Model (RLM) recognizes that relationships are central to doing leadership and posits that leadership is process-oriented, inclusive, empowering, ethical, and purpose-driven (Komives, et al., 2013). Through these five relational leadership components, leaders and group members work collectively to accomplish group goals with a knowing-being-doing process approach: Knowing (knowledge and understanding), Being (attitudes), Doing (skills) (Komives, et al., 2013).

Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model (ELM) effectively aligns with the Relational Leadership Model (Komives, et al., 2013) as follows: RLM’s Knowing and ELM’s Abstract Conceptualization both involve processing knowledge to achieving a level of understanding that translates into demonstrated learning; RLM’s Being and ELM’s Active Experimentation both involve conceptualizing the planned action; RLM’s Doing and ELM’s Concrete Experience both encompass real work, providing the experience component; and ELM’s Reflective Observation, essential to fully processing the experience and key to transforming it into lasting knowledge, aligns with and revisits RLM’s Knowing stage (i.e., the process of reviewing, reflecting, and achieving a deeper level of understanding as one processes the knowledge gained through the experience) (refer to Figure 2).

Owen (2011) emphasized that the “learning and development of leadership capacities are inextricably intertwined” (p. 109). In combining RLM and ELM, classroom leadership instruction is augmented as the leadership learning is situated in students’ experiences of putting leadership knowledge into leadership practice, of reflecting upon and reconstructing the leadership experience in reflective, written activities and discussions where they can construct meanings that can inform and transform their learning experience and ways of exhibiting leadership.

Figure 2. Aligning the Relational Leadership Model (RLM) with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model (ELM)

Forming Partnerships

Guided by the learning objectives of the respective leadership education programs in Student Affairs and Academic Affairs, collaborative efforts began with faculty-led workshops at the Student Affairs annual program for student organization executive board leadership training. These non-credit leadership trainings were well received, and faculty were invited to offer additional non-credit workshops within various Student Affairs programs. These initial collaborations opened conversations for additional collaborative opportunities guided by the tenets of the Experiential Learning Model (ELM) and the Relational Leadership Model (RLM), including a special topics course for new student orientation leaders which led to additional credit-earning special topics courses and a credit-earning leadership practicum.

Special Topics & Practicum Courses. Credit-earning special topics courses in the Bachelor of Arts in Organizational Leadership are those which offer “specialized topics of interest to students of leadership and the organizational community” (NKU, 2018, p. 390). Students may complete up to four unique leadership special topic courses during their undergraduate education. Two organizational leadership special topic courses were developed in partnerships across university divisions: (1) Student Orientation Leadership Development in partnership with Enrollment Management’s department of New Student Orientation and (2) Servant Leadership in Higher Education in partnership with the Student Affairs Office of Student Engagement.

Student Orientation Leadership Development. The first topic course, Student Orientation Leadership Development, provided orientation leaders with a foundation in leadership theory, the first-year college experience, student orientation, and student leadership development. Because the course was specific to incoming student orientation leaders, registration was permit-restricted to new and returning student orientation leaders. Assessment included examination and written reflections of active learning and experiential small group exercises.

The office of New Student Orientation faced a dilemma when planning to offer the course again the following year. Topics courses of the same title and content cannot be repeated; thus, returning student orientation leaders could not retake the course for ongoing orientation leadership training and development. A repeatable alternative was needed to meet new and returning student orientation leader development needs. Further, in anonymous course evaluations, students revealed a need for practical application of course principles with comments such as:

-

- I learned theories but not how to apply them.

- I feel as though it should have been more of “showing” how to be a leader, not a “telling” of how to be a leader.

After reviewing program needs and student feedback, two outcomes emerged: (1) a second topic course, Servant Leadership in Higher Education, to fulfill the interests of students considering a career in higher education and/or Student Affairs and (2) a practicum course specifically for orientation leaders with an increased focus on practical application through active and experiential learning (refer to Table 2 for example course activities).

Servant Leadership in Higher Education. The second organizational leadership special topics course was developed in response to expressed student interest. Many students saw the permit-restricted orientation leader topic course (and later, the practicum that replaced it) listed in the university course catalog, but were disappointed to learn that registration was restricted to students who had applied and been accepted into the student orientation leader program. In response to this interest, the Servant Leadership in Higher Education topics course was developed and delivered by the Assistant Director of Leadership Development in the Office of Student Engagement. The course provided a comprehensive introduction to the work and practice of Student Affairs in the context of American higher education and servant leadership within the context of Student Affairs practice. Open to all students of sophomore class standing or higher, the course has been offered twice on a two-year rotation and is being considered as an ongoing offering to be available once every two to four years.

The Servant Leadership in Higher Education special topic course is hybrid in design with a combination of class meetings and practical experience. Guest lecturers from campus Student Affairs departments (e.g., Office of the Dean of Students, Greek Life, Student Life, Student Housing, Disability Services, Center for Student Inclusiveness, Student Engagement, Office of Title IX, etc.) enrich the classroom experience by sharing their personal expertise in presentation and open discussion. Students learn about various campus Student Affairs departments and choose two for which they serve in an internship capacity, one in each half of the semester. These mini-internships provide opportunities to observe and apply course concepts as students experience the daily activities in their selected Student Affairs departments.

Approximately 30% of course assessment is based on quizzes and a final exam; another 10% focusses on graduate school exploration-related assignments; and the remaining 60% includes reflective, active, experiential learning exercises such as personal statements, weekly reaction papers, and internship presentations. Students develop two personal statements that describe their education and career goals for the purposes of graduate school and/or employment opportunities. One statement is completed in the first week of classes and, after instructor and/or peer feedback, a revised version is completed and submitted in the final week of the course. In their weekly reaction papers, students reflect on the internship experience in-progress and connect their experience to at least two concepts from the course material in each reflection, thereby demonstrating both a full understanding and meaningful application of the concepts. These reflections also serve to guide students as they develop and deliver class presentations about their applied knowledge and learning experiences obtained during their Student Affairs mini-internships.

Leadership Practicum for Student Orientation Leaders. The organizational leadership practicum is a repeatable, variable credit course (1-6 semester credit hours) depending on hours worked in “supervised application-based work experience related to the Leadership major” with the “educational component coordinated among organization, student, and faculty” (NKU, 2018, p. 390). The leadership practicum course structure worked well for orientation leader development given the nature of their training and the course’s variable credit and repeat option. New orientation leaders are eligible for one semester academic credit hour, and experienced, senior orientation leaders (i.e., those who have previously served as orientation leaders and who are returning with greater responsibility and who assist in training and mentoring the developing orientation leaders) are eligible for up to three semester credit hours based on approval of the supervising instructor. The practicum is scheduled each spring and is permit restricted to those who are accepted into the student orientation leader program.

The practicum course is structured in a hybrid delivery format consisting of face-to-face orientation and weekly instructional sessions and six online discussions that extend those conversations in course dialog and reflective learning through peer discussion. In the initial face-to-face class meeting, expectations are outlined and a shared vision and contract is produced. Subsequent class sessions include campus tour training, leadership education, communication, teamwork, navigating conflict, overcoming adversity, and celebrating diversity. In addition to the online discussions and face-to-face class sessions, students are required to meet with each fellow orientation leader throughout the semester and document the meeting with a photograph and written reflection that connects the experience to course concepts. These reflections are submitted to the supervising instructor on a weekly basis. A final reflective report summarizes the student orientation leader practicum experience and must include connections to the organization mission and the personal learning objectives established in the initial course contract. The report must also demonstrate an understanding of the value in appreciating the diverse personalities and leadership strengths of those they work with. The course is graded, and students must earn a grade of B or higher to serve as an orientation leader in the upcoming summer orientation session.

Partnership Outcomes

The initial collaborative efforts (faculty-led workshops) between Student Affairs and Academic Affairs spurred further collaborations and strengthened relationships across institution divisions. Although our partnership growth was essentially organic in nature, naturally evolving as we recognized the potential for additional collaborative efforts, the benefits are ongoing in terms of shared expertise and student learning outcomes as well as mutual program exposure.

Shared Expertise. Student Affairs, Enrollment Management, and the organizational leadership academic program leveraged their collective knowledge and experience when planning student development events that could draw on organizational leadership faculty areas of expertise (e.g., leadership theory and application, organizational theory, followership, ethics, and teamwork). They then recruited applicable faculty to collaboratively design and deliver workshops and informational sessions. Student Affairs and Enrollment Management experts collaborated with experienced faculty for course design. In addition, professionals from Student Affairs and Enrollment Management also served as adjunct professors in organizational leadership for special topics courses, such as Servant Leadership in Higher Education, or the discipline’s introductory foundations of leadership courses. For example, the topics course and subsequent practicums for student orientation leader development were taught by Enrollment Management’s New Student Orientation director.

Experiential Student Learning Outcomes. Owen (2011) emphasized that leadership educators must “purposefully foster learning that helps students integrate knowledge, skills, and experiences in meaningful ways” (p. 109). Infusing experiential learning strategies following Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Model with an emphasis on the Relational Leadership Model’s knowing-being-doing approach to leadership development (Komives et al., 2013), provided a framework to achieve these goals. Students’ reflective writing in each course revealed rich and meaningful introspection with a growth in self-awareness and an increased understanding of and capacity to value others’ perspectives, concepts that are essential to student leadership development programs (CAS, 2018). Additional CAS (2018) SLP-emphasized competencies, such as establishing a sense of purpose, working collaboratively, and managing conflict, were also revealed in both written reflection and interactive course dialog.

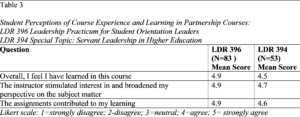

Students’ course evaluations administered centrally from the Office of the Provost via password protected student log-in at the end of the semester provided meaningful data of course outcomes. Student responses are stored on secure servers with no identifiable information and released to faculty via password protected downloadable files. For both courses, student evaluation responses indicated an overall highly positive experience regarding course assignments, stimulated interest in the topic, and instructor effectiveness as measured on a Likert scale of one to five (1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=neutral; 4=agree; 5= strongly agree) (refer to Table 3). Qualitative observations were especially revealing as noted in the following comments:

LDR 396 Leadership Practicum for Student Orientation Leaders

- Class discussions on Blackboard were mentally stimulating

- discussions in class were enlightening

- helped me become a better leader and gain a better understanding of my leadership style

- I learned a lot about myself and how to be a better leader.

LDR 394 Special Topic: Servant Leadership in Higher Education

- I am very thankful that I took this course, as the assignments and internships allowed me to gain a lot of knowledge in student affairs.

- The internship reflections and presentations were useful for applying course concepts to real life situations, the quizzes were helpful in learning the course material, and the graduate school assignment and personal statement were helpful for the graduate applications

- The internships with the class contributed to my learning

- We were able to work in an internship setting. I learned so much from participating in this course

- The internships gave me the chance to work with other offices on campus, try new things, and get experiences that will help me as I apply to graduate school

Inspired by these outcomes, plans are underway to invite course alumni to return to campus for focus group discussions and, for those who are unable to attend the focus group, phone or Web-based interviews. These sessions will provide qualitative data from past participants that will help us improve our understanding of students’ lived course experiences, identify long-term influences, and identify opportunities to strengthen these leadership education and development opportunities.

Program Exposure. As a result of the initial partnership between Student Affairs and an academic organizational leadership undergraduate degree program, nearly 300 students have participated in one or more academic credit-earning leadership development opportunities over seven academic semesters. Two thirds of these students applied the earned hours as elective credit and a third of the students graduated with either a major or secondary area of study (minor or focus) in the academic leadership program. Similarly, organizational leadership majors who were unaware of the non-credit bearing leadership development opportunities available on campus were introduced to these co-curricular campus engagement initiatives.

Although program growth was not the focus of the collaborative partnership, the value of this unintended outcome cannot be underestimated. When students are not engaged on campus or do not form campus connections, motivation decreases and retention toward degree completion is at risk (Tinto, 1993). Any opportunity to facilitate connections between students and campus organizations can potentially contribute toward student engagement, retention, and persistence. In addition, it is relevant that anecdotal reports indicate that some students who participated in the collaborative efforts have gone on to pursue a graduate degree in Student Affairs as a direct result of their experiences. We are intrigued by this outcome and expect the planned qualitative research from follow-up focus groups and interviews with student participants and alumni will provide additional insight into their lived experiences in these institutional partnerships and how these experiences informed their leadership development.

Recommendations

Institutions that offer both credit and non-credit bearing leadership education but have not yet engaged in collaborative efforts should start the conversation and explore the possibility. The collaborative relationships described in this article evolved organically from a serendipitous conversation that ultimately filled a Student Affairs division’s need for a workshop facilitator. From that conversation, institutional partnerships grew as did the collaborative efforts, resulting in additional shared expertise, special topics courses, and a leadership practicum for student orientation leader development. Each program has been enriched as have the leadership learning experiences of the students they serve. Institutions that are not yet leveraging their collaborative partnership potential should get started: (a) schedule a meeting between relevant stakeholders in Academic Affairs and Student Affairs divisions; (b) review and become informed about each program’s mission, vision, and goals; (c) identify shared objectives and strengths; (d) brainstorm to identify a collaborative opportunity; (e) develop and deliver the initiative; (f) assess the outcomes; (g) review and revise for the next collaborative effort. When kickstarting the process, follow recommended guidelines for leadership education program planning and assessment.

Planning and Assessment. If the institution’s Academic Affairs and/or Student Affairs divisions have not adopted or established guidelines for planning and assessing their leadership programs, highly recommended sources include the CAS Standards for Leadership Programs, CAS Self-Assessment Guides (SAGs), and ILA’s Guiding Questions for Leadership Programs (Owen, 2012).

CAS standards. The Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS), a consortium of higher education professional associations that are dedicated to enhancing and ensuring the quality of student programs and services that are offered to students in higher education, developed Standards for Leadership Programs (SLPs) in 1995 and revised them in 2009 and 2018 (CAS, 2018). The SLPs include twelve general standards that provide common criteria for each functional area (refer to Table 4). Within each general standard, functional area standards include specific guidelines and standards targeted to each specialty. In addition, CAS offers a set of SLP Self-Assessment Guides (SAGs) that ensure formative, structured programmatic self-assessment in context with the CAS SLPs. These CAS resources offer guidelines for both Academic Affairs and Student Affairs professionals that can help to ensure that student leadership learning opportunities and experiences facilitate student learning and student development toward becoming engaged contributors to their communities. For detailed information regarding the effectiveness of CAS SLPs, refer to the National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs’ Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership that examined the design and delivery of collegiate leadership studies across 89 institutions (Owen, 2012). Findings indicate that “leadership educators who make good use of the CAS SLPs may more effectively assess leadership program design and delivery, better advocate for necessary resources, and make increasingly effective programmatic decisions (Owen, 2012, p. 18).

ILA Guiding Questions. Established in 1999, the International Leadership Association (ILA) has become the largest international, inter-disciplinary organization devoted to the study and development of leadership (ILA, 2019). The ILA was created to extend the leadership conversation beyond discipline or region and provide an interdisciplinary, international context that spans educational, public administration, for-profit, and non-profit sectors. The ILA’s Guiding Questions were produced to assist individuals from across these diverse sectors in curricular leadership development, revision, and assessment (ILA, 2009) (refer to Table 5). A series of guiding questions consist of an overarching question in each of five key topic-specific sections (context, conceptual framework, content, teaching and learning, and outcomes and assessment). The tool can be used in one of two ways: (1) a comprehensive approach to the general guiding questions, particularly if the program is still in the early planning stages, or (2) a more focused approach on any key topic by addressing the questions in appropriate sections. The ILA Guiding Questions can be used in conjunction with CAS Standards and Self-Assessment Guides for robust program planning, development, and assessment.

Conclusion

The National Leadership Education Research Agenda explains that leadership education is “the pedagogical practice of facilitating leadership learning in an effort to build human capacity and is informed by leadership theory and research. It values and is inclusive of both curricular and co-curricular educational contexts” (Andenoro, Allen, Haber-Curran, Jenkins, Sowcik, Dugan, & Osteen, 2013, p. 3). Although research has shown the value in both Student Affairs and Academic Affairs approaches to student leadership education and development, many programs continue to operate independently (Manning et al., 2006; Owen, 2012). CAS Standards and Guidelines for Student Leadership Programs (CAS, 2018) emphasize that “it is essential that campuses seek to develop comprehensive leadership programs and recognize the need to make integrative leadership learning opportunities available to all students through coordinated campus-wide efforts” (p. 4). Opportunities abound for leadership educators to provide meaningful, experiential leadership learning through formative partnerships that cross curricular and co-curricular boundaries.

Collaborative outcomes developed through institutional partnerships, such as the practicum and special topics courses and faculty-led workshops described in this paper, offer opportunities to enhance existing programming, provide students additional opportunities to develop leadership experience, and inspire students’ lifelong development through involvement in structured leadership experiences during their collegiate careers. Wheatley (2006) explains that “leadership is always dependent on the context, but the context is dependent on the relationships we value” (p. 144). Student Affairs, Academic Affairs, and other campus partners should seize the opportunity to move beyond traditional classroom and university divisions and create working relationships to facilitate new ways of offering their students experiential leadership education that leverages cross-campus collaborations.

References

Andenoro, A. C., Allen, S. J., Haber-Curran, P., Jenkins, D. M., Sowcik, M., Dugan, J. P., & Osteen, L. (2013). National Leadership Education Research Agenda 2013-2018: Providing strategic direction for the field of leadership education. Retrieved from Association of Leadership Educators website: http://leadershipeducators.org/ResearchAgenda.

Baxter Magolda, M. B. (1999). Creating contexts for learning and self-authorship: Constructive developmental pedagogy. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Bonwell, C. C. & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1. Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

CAS, Council for Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2018). CAS Standards for programs and services: Student leadership programs. Fort Collins, CO: CAS.

CAS, Council for Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2019). About CAS: Mission, Vision, and Purpose. Retrieved from: http://www.cas.edu/mission

Chickering, A. W. & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven Principles for Good Practice. American Association for Higher Education, Washington, D.C. AAHE Bulletin 39. pp 3-7.

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. School Journal, Volume LIV No. 3. 77-80.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education. NY, New York: Collier Books.

Guthrie, K. L., Teig, T. S., & Hu, P. (2018). Academic leadership programs in the United States. Tallahassee, FL: Leadership Learning Research Center, Florida State University.

International Leadership Association (ILA). (2009). Guiding Questions: Guidelines for Leadership Education Programs. Silver Spring, MD. Retrieved from: http://www.ila-net.org/Communities/LC/GuidingQuestionsFinal.pdf

International Leadership Association (ILA). (2019). About the ILA. Retrieved from: http://ila-net.org/About/index.htm

Kolb, A. & Kolb, D. (2005). Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4, 193-212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Komives, S. R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T. R. (2013). Exploring leadership: For college students who want to make a difference. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Manning, G. & Curtis, K. (2019). The art of leadership (6th Ed.) New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Manning, K., Kinzie, J., & Schuh, J. (2006). One size does not fit all. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

National Association of Colleges and Employers (2008). Experiential education survey. Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers.

NKU (2018). Northern Kentucky University (NKU): Undergraduate catalog 2018-2019. Retrieved from: https://inside.nku.edu/registrar/catalog.html

NSEE, National Society for Experiential Education (2013). Eight principles of good practice for all experiential learning activities. Presented at the 1998 Annual Meeting, Norfolk, VA. Last Updated on Monday, December 09, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.nsee.org/8-principles

Owen, J. (2011). Considerations of Student Learning in Leadership. In Susan R. Komives, John P. Dugan, Julie E. Owen, Craig Slack, Wendy Wagner, & Associates (Eds.) The handbook for student leadership development (2nd Ed.). pp. 109-133. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Owen, J. E. (2012). Findings from The Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership Institutional Survey (MSL-IS): A National Report. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Seemiller, C. & Priest, K. L. (2015). The Hidden “Who” in Leadership Education: Conceptualizing Leadership Educator Professional Identity Development. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(3), 132-151. https://doi.org/10.12806/v14/i3/t2

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

Van Vugt, M. and Ahuja, A. (2011), Naturally Selected: The Evolutionary Science of Leadership, Harper Collins, New York, NY.

Wheatley, M. J. (2006). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world (3rd Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler.

Yukl, G. (2012), Leadership in organizations (8th ed.), Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.