Introduction

Counter-reality, or the pervasive and persuasive replacement of objective truths with subjective opinions grounded in falsehoods, is a prominent fixture in the landscape of global information dissemination. Grounded in the work of denialism (Specter, 2010), counter-reality spreads falsehoods created by an accumulation of alternative facts, related biases, prejudices, and the omissions of verified, empirically based, and truthful statements. Concurrently, counter- reality and pervasive misinformation are presented on nearly a daily basis via today’s rapidly growing assortment of informal information outlets, i.e. blogs, vlogs, podcasts, and social media. These informal information outlets often present skewed facts and subjective biases, creating an environment where decisions can be made without critical information and dialogue. These outlets and the associated issues are a significant problem for leadership educators attempting to foster critical thought and effective knowledge consumption within leadership students.

However, the development of agency, that is the development of the propensity to act based on an understanding of the past, context for the present, and foresight for the future, and effective decision-making processes can foster curiosity and critical thinking necessary for questioning counter-reality and making judgements that spark action for addressing the world’s most challenging problems (Andenoro, Sowcik, & Balser, 2017).

Teaching leadership students to evaluate “truth” through the lens of objectivity can provide students with the tools to be more perceptive and intentional when faced with complex problems. Stedman and Andenoro (2015) note that “the human race is responsible for two things, identifying the problems we face and solving them” (p. 145). To do this, leadership students must be equipped with the skills to synthesize and compile ideas from various perspectives and use them effectively to address environmental and societal complexity. “This may be one of the grand challenges of leadership educators” (2015, p. 146).

Agency (Andenoro, Sowcik, & Balser, 2017; Biesta & Tedder, 2007; Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, & Paloniemi, 2013; Gallagher, 2007; McNay, 2004) is a multifaceted cognitive, affective, and behavioral approach grounded in psychology. For the purposes of this paper, agency will be defined as the propensity to act based on an understanding of the past, context for the present, and foresight for the future (Andenoro, Sowcik, & Balser, 2017).

Agency is grounded in the process of self-determinism (Ferré, 1973) and provides students with the tools for challenging counter-reality. Without the development of agency and the motivation to seek truth, opportunities exist for leaders to be open to alternative facts. This has the potential to spread false beliefs to followers allowing alternative facts to become ingrained within the fabric of truth and reality for students.

There is an infinite array of ambiguous global knowledge that leadership educators and students fail to understand or have yet to discover. The most influential leaders of tomorrow will not only seek to solve the problems we have discovered, but seek to find sustainable solutions to future issues. Through the use of agency and effective decision-making grounded in incisive questioning, an objective and truth-based reality can emerge for leadership students and dispel the counter-realities that plague global societies. Further, the development of agency combined with the critical development of incisive questioning of counter-realities can spur new perspectives in leadership students that enhance their ability to find, understand, and address complex issues. This paper presents an intentionally designed learning methodology, based on the F.A.C.E. Method (Andenoro, 2014; Andenoro & Stedman, 2015; Stedman & Andenoro, 2015), that leadership educators can use to develop of agency and effective decision-making within interdisciplinary leadership students despite pervasive societal counter-reality.

Literature Review

Agency. Agency is the propensity to act with an understanding of the past, context for the present, and foresight for the future (Andenoro, Sowcik, & Balser, In Press). Individuals practice agency when they consciously decide to actively engage with issues surrounding them (Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, & Paloniemi, 2013). Agency emerges when students practice self-reflection and self-evaluation (McNay, 2004) with respect to the complex problems they are attempting to address. Due to its grounding in the subjects’ experience of the world (2004), through agency, students develop a deeper sense of engagement and take ownership of the problems within their contexts.

Participation and learning are ontogenetically linked to individuals’ academic and professional identities and actions. The students’ accounts of experiences provide context for their role within the given situation and their decision about what problems are worth solving, and with what degree of energy (Eteläpelto, et al., 2013). Through the practice of agency, leadership students develop the potential for increased understanding of current problems and develop the ability to address future problems grounded in reliable schema (Andenoro, Sowcik, & Balser, 2017; Bajaj, 2005; Boyte, 2008; Manis, 2012). Thus, properly-informed perspectives can inspire leaders to engage with and address critical local and global complex problems.

In addition to gaining perspective through agency, the ability to address counter-reality is grounded in the development of leadership students’ self-efficacy, or the confidence in one’s understanding of their own abilities (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy and agency are positively correlated (Bandura, 2000; Bandura, 1990; Bandura, 1982), thus individuals with poor self- efficacy often exhibit poor agency. Those with high self-efficacy also have active agency, defined as the exertion of intentional influence on one’s life and circumstances of living (Eteläpelto, et al. 2013). Therefore, if leadership educators develop students’ agency, teach students how to survey their surroundings, and encourage them to ask questions that reveal crucial and reliable information about target issues, the students’ perspectives will expand along with their confidence to evaluate counter-reality and solve critical issues (Reeve & Tseng, 2011).

Counter-Reality. Specter (2010) notes that while denialism is rarely malevolent, it subconsciously combines fear of change and misguided desires for personal health or gain. Denialism can be likened to counter-reality, or the pervasive and persuasive replacement of objective truths with subjective opinions grounded in falsehoods, alternative facts, their related biases, prejudices, and the omission of verified, empirically based, and truthful statements.

Counter-reality is problematic for leadership students, as their decisions, conclusions, and resulting explanations are often based on a synthesis of their experiences, emotions, and intuition. Concurrently, students rarely follow the principles of probability theory in judging the likelihood of uncertain events (Kahneman, & Tversky, 1972). Counter-reality is problematic for future leaders needing to make decisions that impact the future of their organizations. Relying on individual judgement is often to the detriment of the organization, as leaders frequently fail to consider empirically-based research and credible facts, and make decisions based simply on their personal experiences and beliefs. Accordingly, intuitive predictions are insensitive to the reliability of the evidence, the probability of the outcome, and in violation of the logic of statistical prediction (Kahneman, & Tversky, 1973). Intuitive predictions reaffirm counter- reality and can result in the most important decisions of leaders being based on beliefs and the likelihood of uncertain events (Tversky & Kahneman,1975). This phenomenon occurs because students rely on a limited number of heuristic principles that reduce complex tasks of assessing likelihoods and predicting values to simpler judgmental operations. In an attempt to create simplicity within their environments, students reduce the unknown by making assumptions. In general, these heuristics are quite useful, but sometimes lead to severe and systematic errors (1975). Therefore, an unaware leadership student may make decisions based in counter-reality if they are not taught how to critically evaluate decisions with a holistic understanding of the situational complexity. If leaders do not develop the ability to take diverse perspectives into account, then it is probable that when faced with the difficult task of judging probability or frequency, they will employ a limited number of heuristics which will reduce complex judgments to simpler ones (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). More concisely, if complex issues are reduced to simple problems and are met with simple solutions, the essence of the original problem will remain unresolved.

Agency, Decision-Making, and Counter-Reality. Choice is a maximization process and optimal decisions increase the chances of survival in a competitive environment (Tversky & Kahneman, 1986). Further, leadership students need to develop a sense of rationality to increase their chances of effectively pursuing their goals (e.g., creating solutions to complex problems) (Daft, 2007; Griffin & Moorhead, 2011; Scott & Davis, 2015). The necessity of improved rationality and critical thinking when evaluating issues arises from the consequences that can occur when decisions are made in error. Most daily decisions are supplied by habitual practices. However, an emergency occasionally occurs. In these cases, individuals subconsciously realize it quickly and fast thinking, or rapid cognition (Isenman, 2013), supplies an automated and instantaneous response, which is often fully adequate. In this context, students are not differentiated from animals, as instinct and intuition are engaged in the decision-making process. Unfortunately, fast thinking is not always appropriate or sufficient. Slow thinking, or more reflective and intentional thinking, takes over. Slow thinking is engaged reluctantly, and is associated with large effort and significant energy depletion. If a habitual answer is supplied, it often takes an effort to question it (Kahneman, 2011). Many students lack the motivation and capacity to effectively employ reflective and intentional thinking practices that question the validity of their perspectives. For example, a leader’s actions may not have a foreseeable result, and without thinking intentionally, the leader may willingly engage in risk with optimism in hopes of improving the current organizational condition. Decision-making coupled with risk can be viewed as a choice between prospects or gambles (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Without agency choices grounded in predictive uncertainty are made without advance knowledge of their consequences. Because the consequences of such actions depend on uncertain events, the individual’s choice to act may be construed as the acceptance of a gamble that can yield various outcomes with different probabilities (Kahneman, & Tversky, 1984). Logically then, leaders should practice agency, or make decisions with an understanding of the past, context of current issues, and foresight of future problems before “accepting” a risk.

It is not enough for a leader to simply choose between a sure loss and a substantial probability of a larger loss based on their perceptions (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). That would be considered risk seeking behavior. Leadership students must be taught that there is no substitution for the facts and knowledge presented via reputable sources. How students think about those facts is framed by the questions that are asked about the facts. Therefore, if students are taught how to ask incisive questions, then how they frame questions about facts and alternative perspectives will be shifted to extend beyond their current socially constructed schema. Expanding perceptions, ultimately will allow leaders to think about the complexity of the challenges they face and address them creatively.

Students can develop the practical-evaluative dimension of agency that is necessary to adapt to a particular situation by understanding the way in which individuals bring their past experiences and future orientations to bear on the present situation (Biesta & Tedder, 2007). Agency enables leadership students to develop heightened awareness and understanding of the context surrounding complex issues in our world and uses the past to inform the future giving leadership students the opportunity to use history in the formation of incisive questions.

Leadership students acquire agency by understanding how to incisively question the world by comparing untrue limiting assumptions to true liberating assumptions. Kline (1999) notes, that thinking, feeling, decision-making, and action are driven by assumptions. Innovative ideas and authentic feelings come from true liberating assumptions (1999). Conversely, stagnant ideas stem from untrue and limiting assumptions. For example, an untrue limiting assumption might be “I am a victim of time constraints.” An alternative liberating true assumption would be, “I have a choice about how I spend my time.” Therefore, the incisive question that can be asked is: “if you knew that you have a choice, how would you restructure your time?” Being able to frame and answer these questions can shift students’ perspectives and facilitate a higher awareness that improves their abilities to make decisions (1999), especially when operating under risk.

Description of the Application

Experiences that ground agency and decision-making in objective facts and empirical evidence in the face of counter-reality create an innovative opportunity for leadership students. Leadership educators can promote student engagement through praxis creating reciprocal learning, challenging counter-reality, and building agency. Supported by the behavioral economic ideologies of Tversky and Kahneman (1992; 1986; 1975; 1973), leadership educators can shift perspectives and change behaviors of leadership students. Leadership educators can facilitate contextual experiences which build capacity for agency in leadership students and can lead to sustainable solutions for the future for organizations and communities. The following provides context and a process for facilitating a powerful leadership education opportunity with interdisciplinary students in higher education settings and beyond.

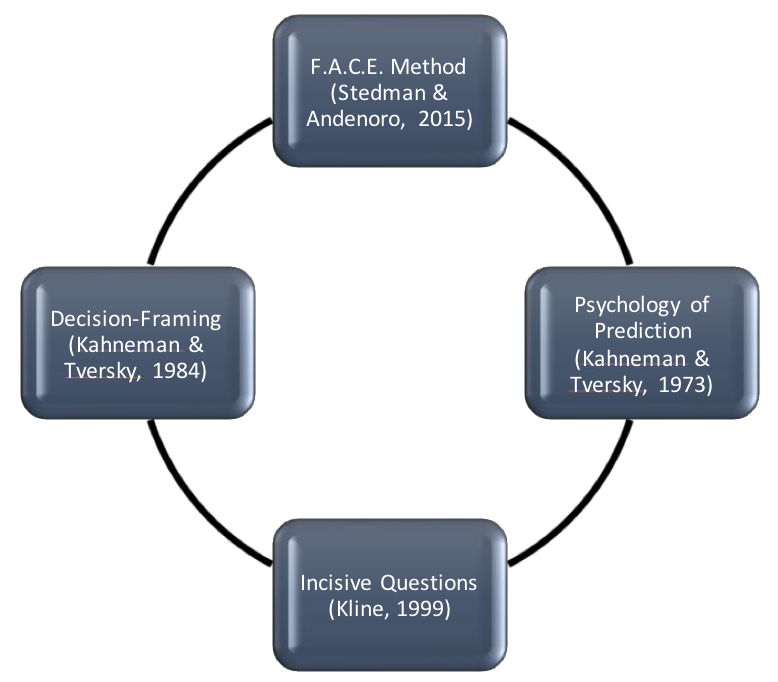

The power of the learning experience engages several critical approaches, the F.A.C.E. Method (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015), decision-framing (Kahneman & Tversky, 1984), the psychology of prediction (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973), and incisive questioning (Kline, 1999), in a multi-step approach grounded in the psychology of choice and the attitudes and cognitive schemas that produce good decisions. The following provides a model for the theoretical foundations that guide the previously articulated learning methodology aimed at the development of agency within the face of counter-reality. The model is followed by the process’ outlined learning stages.

Figure 1: Theoretical foundation for learning methodology.

Stage 1 – Exposure. The [insert program] at [insert context] creates opportunities for students in an interdisciplinary undergraduate course that unpacks the ambiguity of complex problems and considerations to explore and address local and global issues as “experts” replete with the knowledge, skills, and capacities necessary for developing sustainable solutions.

Students in the leadership education context listen to content experts, review articles, and solicit perspectives from outside sources surrounding the presented complex problems. An example of this is an economist and global fund manager sharing perspectives about the economic and political dynamics associated with the international oil markets. Consistent with the work of Kahneman & Tversky (1973), the first stage effectively sets the foundation for synthesizing large amounts of data and applying them within the decision-making process.

Stage 2 – Foundational Awareness. This is the first reflection point in establishing Emotionally Engaged Thinking, the outcome of the F.A.C.E. Method (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015), and the development of complex adaptive leadership capacity and agency. Through foundational awareness, students constructively identify and explore their emotions in relation to a given situation (Andenoro & Stedman, 2015). Students are encouraged to process through their feelings surrounding the ambiguity and competing counter-reality present in the issue or context. During this stage, educators guide students to develop authentic relationships with the problem, understand its application to current contexts, and broad societal implications (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015). Subtle questions like, “what does this make you think of?”, “what do you know about this?”, and “how does this make you feel?” allow students to unpack emotions and experiences linked to the issue. This is critical from an active learning perspective and creates an authentic relationship between the students and the issue. In addition, a foundation for the next stage is created as students begin to build useful schema for addressing the issue. The foundational awareness stage also allows students to explore moral conflicts or dilemmas that may arise as the schema progresses within the context.

Stage 3 – Authentic Engagement. The idea of authentic engagement is grounded in one’s ability to truly empathize with the problem and the individuals affected (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015). Authentic engagement builds upon foundational awareness in the previous step asking the students to position themselves within the context of the issue. The stage connects the student with the problem, establishing ownership and a commitment for addressing it. Again subtle, but intentional, language can be used by the instructor to encourage the commitment. A well-placed question like, “something needs to be done about this, right” or “is this unacceptable”, requires students to affirm their commitment to addressing the problem.

While they may not understand how to effectively address the issue, the student develops responsibility with respect to the problem in this stage (Andenoro, 2014). Rationality and emotion are intertwined within authentic engagement as students reflect upon their understanding and expectations of the situation. Authentic engagement is critical to addressing counter-reality, as the stage creates a context for students to make decisions about the situation grounded in an understanding of their feelings and ownership for the problem. Key behaviors of authentic engagement include attentive listening, productive dialogue, and reflective thought (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015).

Stage 4 – Connective Analysis. The fourth stage gives holistic meaning to the experience or problem. Through Connective Analysis, systems thinking reveals how the student’s perspectives can be synthesized with other contextual perspectives thus creating a more holistic picture of the situation (Andenoro & Stedman, 2015). During this phase, students explore counter ideas, emotions, and reactions within the same experience or problem. The systems understanding stemming from connective analysis provides a connection to others while taking new possibilities into account within the scope of their context (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015). Exercises should include mind maps or concept models guiding the students through the process of determining the critical systems for consideration. Further, questions should force students to a place of deep learning in an effort to gain a holistic understanding of the issue and the related context. This stage sets the foundation for adaptive solution building and by association, predisposes the students to practicing adaptive leadership (Heifetz, Grashow, & Linsky, 2009).

Stage 5 – Empowerment & Change. The final phase moves participants from the development of progressive attitudes to the accompanying behaviors. Behaviors stemming from this step form the foundation for influencing others and building large-scale organizational and community change (Stedman & Andenoro, 2015). Further, it assists the student in challenging the status quo and foreseeing potential outcomes if the new possibilities are implemented (Odom, Andenoro, Sandlin, & Jones, 2015). A critical piece of this stage is the development of an action plan providing strategic direction for addressing the issue. Students in this stage are asked the question, “what are you going to do?” This implies that action is necessary and forces the student into a process of reflection and critical thinking. Specificity is key in creating actionable tasks, so the leadership educator should prioritize this with students to promote sustainably addressing the issue. Accountability structures are also built into the learning context to maximize motivation and follow-through for the associated tasks.

This innovative approach has powerful implications for leadership students. It validates the fundamental obligations of modern universities to intentionally influence the moral thinking and action of the next generation of leaders and citizens (Whiteley, 2000), has the potential to be a catalyst for enhanced organizational practice and community sustainability (Odom, Andenoro, Sandlin, & Jones, 2015), and creates the impetus for influencing sustainable change and creating solutions for the complex adaptive challenges that exist within our ever-changing world.

Discussion of Outcomes

To date, findings regarding the impact of this process grounded in Emotionally Engaged Thinking, have indicated that there is tremendous benefit to students engaging in environments (Andenoro, Bigham, & Balser, 2014). Findings illustrate that students show elevated levels of adaptive leadership capacity (inclusive of self-awareness, intercultural competence, desire for and understanding of collaboration, effective communication, and internal locus of control), systems thinking, and socially responsible agency (2014). However, when adaptive leadership capacity, systems thinking, and socially responsible agency are joined with innovative experiential leadership education aimed at instilling process-based confidence and expertise in interdisciplinary students, a tremendous educational environment with significant implications for addressing complex problems emerges.

Preliminary qualitative findings collected through informal ethnography and content analyses (Erlandson, Harris, Skipper, & Allen, 1993) and analyzed through cursory constant comparative analyses (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) indicate that interdisciplinary undergraduate students are demonstrating depth of thought, increased levels of awareness, the ability to foreshadow potential complex consequences of their decisions, and improved agency for addressing and mitigating complex adaptive situations, due to this educational methodology. Through the innovative approach described above, leadership educators can go beyond the traditional educational methods of teaching about complex problems to create critical affective shifts and behavioral changes in leadership students. Our approach serves as a powerful tool, equipping leadership students with the capacities and dispositions to make decisions that increase sustainability of our organizations, supplement inclusive community development, and create opportunities for a more socially just society. Our method creates the foundation for students to be the stewards of a better future and paves the way for adaptive leadership capacity, agency, and sustainable solutions that have far reaching implications for our world.

Reflections of the Practitioners & Recommendations

It is paramount that leadership educators and leadership students care about their depth of understanding and accompanying agency when evaluating reality. Tangible connections and implications for this process can be found in the first, third, and sixth priorities listed by the National Leadership Education Research Agenda — Teaching, Learning & Curriculum Development, the Psychological Development of the Leader, Learner, and Follower, and Social Change and Community Development, respectively (Andenoro, Allen, Haber-Curran, Jenkins, Sowcik, Dugan, & Osteen, 2013). Furthermore, this process also finds application in the American Association for Agricultural Education National Research Agenda, specifically in the research priority areas four and seven: Meaningful, Engaged Learning in All Environments and Addressing Complex Problems (Roberts, Harder, & Brashears, 2016), respectively. Leadership students cannot solve world problems if they are not taught how to identify those problems.

Through this new lens of agency, there is hope that future leaders will be better equipped to see past counter-realities and nullify situations that perpetuate counter-realities.

When implementing this learning opportunity for interdisciplinary leadership students, it is critical to maintain emotionally intelligent teaching practices. An in depth understanding of self becomes imperative, as self-awareness creates an openness to divergent perspectives (Andenoro, Popa, Bletscher, & Albert, 2012) that may be presented by the students. Self- awareness also creates the foundation for managing emotions as potentially inflammatory comments and perspectives that contrast the educator’s values may be presented within the learning context. An emotionally intelligent approach to teaching and learning can also mitigate the motivational challenges that exist due to the potentially controversial content being presented by both the educator and the students. Finally, it is critical to practice empathy and social awareness for students and their perspectives. It is essential to maintaining a supportive leadership education environment where perspectives and “truths” can be challenged. Educators should shape their language intentionally to validate without providing confirmation of correctness for the students considering that perspectives shared are grounded in experiences and emotions that are often connected to deeply rooted values in the students.

Practically, we are at a critical juncture globally. Divisiveness and polarization are at an all-time high in the United States and global contexts. Political tensions and alternate realities are abundant, making social construction of truth-based realities necessary for decision-making. When coupled with the average leadership student’s dependence on social media and peer-based information, the next generation of leadership students are significantly disadvantaged. By developing leadership education experiences that empower agency and effective decision- making in the face of counter-realities, leadership educators create a space to challenge and construct “truths”. This is the foundation of critical and creative thinking—essential pieces of leadership practice capable of addressing complex problems. This practice is timely, provides a context for supporting truth based inquiry, and builds capacity for leadership students to address complex problems through collaboration and sustainable solution building.

References

Andenoro, A. C. (2014, February). The key to saving 9.6 billion. Proceedings of TEDxUF, Gainesville, FL.

Andenoro, A. C., Allen, S. J., Haber-Curran, P., Jenkins, D. M., Sowcik, M., Dugan, J. P., & Osteen, L. (2013). National leadership education research agenda 2013-2018: Providing strategic direction for the field of leadership education. Retrieved from Association of Leadership Educators website: http://leadershipeducators. org/ResearchAgenda.

Andenoro, A. C., Bigham, D. L., Balser, T. C. (2014, July). Addressing global crisis: Using authentic audiences and challenges to develop adaptive leadership and socially responsible agency in leadership learners. Proceedings of the Association of Leadership Educators, San Antonio, TX.

Andenoro, A. C., Popa, A. B., Bletscher, C. G., & Albert, J. (2012). Storytelling as a vehicle for self‐awareness: Establishing a foundation for intercultural competency

development. Journal of Leadership Studies, 6(2), 102-109.

Andenoro, A. C., Sowcik, M. J., & Balser, T. C. (2017). Addressing Complex Problems: Using Authentic Audiences and Challenges to Develop Adaptive Leadership and Socially Responsible Agency in Leadership Learners. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(4), 1- 19.

Andenoro, A. C. & Stedman, N. L. P. (2015, July). Developing emotionally engaged thinking: Understanding and application for the FACE Method. Proceedings of the Association of Leadership Educators, Washington D.C., USA.

Bajaj, M. I. (2005). Conceptualizing agency amidst crisis: A case study of youth responses to human values education in Zambia (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Bandura, A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current directions in psychological science, 9(3), 75-78.

Bandura, A. (1990). Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of personal agency. Journal of applied sport psychology, 2(2), 128-163.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American psychologist, 37(2), 122.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.

Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 132-149.

Boyte, H. C. (2008). Against the current: Developing the civic agency of students. Change: the magazine of higher learning, 40(3), 8-15.

Daft, R. L. (2007). Understanding the theory and design of organizations. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B. L., & Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: A guide to methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency?

Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45-65.

Ferré, F. (1973). Self-determinism. American Philosophical Quarterly, 10(3), 165-176.

Gallagher, S. (2007). The natural philosophy of agency. Philosophy Compass, 2(2), 347-357. Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Hawthorne,

NY: Aldine.

Griffin, R. W., & Moorhead, G. (2011). Organizational behavior. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Heifetz, R. A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Isenman, L. (2013). Understanding unconscious intelligence and intuition:” Blink” and beyond. Perspectives in biology and medicine, 56(1), 148-166.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. London, UK: Macmillan.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1972). Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness.

In The concept of probability in psychological experiments (pp. 25-48). Springer Netherlands.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973). On the psychology of prediction. Psychological review, 80(4), 237.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society, 263-291.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American psychologist, 39(4), 341.

Kline, N. (1999). Time to think: Listening to ignite the human mind. London, UK: Ward Lock, Cassell Illustrated.

Manis, A. A. (2012). A Review of the Literature on Promoting Cultural Competence and Social Justice Agency among Students and Counselor Trainees: Piecing the Evidence Together to Advance Pedagogy and Research. Professional Counselor, 2(1), 48-57.

McNay, L. (2004). Agency and experience: Gender as a lived relation. The Sociological Review, 52(2), 173–190.

Odom, S. F., Andenoro, A. C., Sandlin, M. R., Jones J. L. (2015). Undergraduate leadership students’ self-perceived level of moral imagination: An innovative foundation for morality-based leadership curricula. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(2), 129-145.

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257-267.

Roberts, T. G., Harder, A., & Brashears, M. T. (2016). American association for agricultural education national research agenda: 2016-2020. Gainesville, FL: Department of Agricultural Education and Communication.

Scott, W. R., & Davis, G. F. (2015). Organizations and organizing: Rational, natural and open systems perspectives. Routledge.

Specter, M. (2010). Denialism: How irrational thinking hinders scientific progress, harms the planet, and threatens our lives. London, UK: Gerald Duckworth & Co.

Stedman, N. L. P. & Andenoro, A. C. (2015). Emotionally engaged leadership: Shifting paradigms and creating adaptive solutions for 2050. In M. J. Sowcik, A. C. Andenoro, M. Mcnutt, & S. Murphy (Eds.), Leadership 2050: Contextualizing Global Leadership Processes for the Future (p. 147-159). Bingley, West Yorkshire, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2), 207-232.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1975). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.

In Utility, probability, and human decision making (pp. 141-162). Springer Netherlands.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1986). Rational choice and the framing of decisions. Journal of business, S251-S278.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and uncertainty, 5(4), 297-323.

Whiteley, J. (2000). Exploring moral action in the context of the dilemmas of young adulthood. Analytic Teaching, 20(1).

Author Biographies

Anthony C. Andenoro, Ph.D., currently serves as a faculty member for the Leadership Studies Program and the Department of Psychology at Iowa State University. His research interests include the neuropsychology of leadership and the development of human capacity for addressing complex organizational and community-based problems. He has an active record of publications and has procured over $3 million in grants and contracts. Email. andenoro@iastate.edu

Linnea M. Dulikarvich serves as an Undergraduate Research Scholar and Political Science and Information Systems major at the University of Florida. Her research interests include the development of Leadership Education learning interventions to shift behaviors and attitudes in interdisciplinary students. She has studied at the London School of Economics and aspires to serve underrepresented populations through the diverse fields of Law. Email. neadulikravich@ufl.edu

Corina H. McBride serves as a Program Associate and Undergraduate Research Scholar with the Challenge 2050 Project and is a Natural Resource Conservation major at the University of Florida. Her research interests include managing change and addressing complex problems in developing contexts, developing sustainability through urban agriculture and alternative energies, and the empowerment of female youth leadership. Email. mcbridecorina@ufl.edu

Nicole L.P. Stedman, Ph.D., is a Professor of Leadership in the Department of Agricultural Education and Communication at the University of Florida. She serves as the Associate Department Chair and Undergraduate Coordinator, while actively publishing, presenting, and partnering for $2.2 million in funded grants. Her research includes critical thinking pedagogy and collaboratively creating Emotionally Engaged Thinking (EET), a model using emotion as a catalyst for decision-making. Email. nstedman@ufl.edu

Jessica Childers, M.S., currently serves as a Research Coordinator for the Department of Agricultural Education and Communication University of Florida. She earned her Master of Science degree in Research and Evaluation Methodology from the University of Florida’s College of Education and specializes in assisting faculty in applying for grant funding and preparing research manuscripts for publication. Email. jchilders@ufl.edu